NICABM Experts

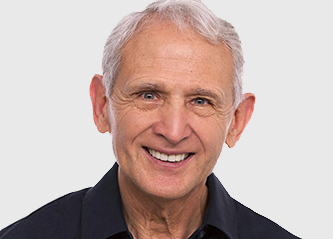

Peter Levine, PhD

Peter Levine, PhD, is a psychologist, researcher, and developer of Somatic Experiencing.[1] The approach was inspired by Peter’s observation of trauma recovery behaviors in nature.

Much of Peter’s work involves understanding the nature of traumatic memory, helping clients get in touch with their bodily responses, and helping clients come out of the freeze response.

He is the author of several books on the treatment of trauma, including Waking the Tiger[2] and In an Unspoken Voice.[3] He is also the director of the Somatic Experiencing Trauma Institute.[4]

What is Somatic Experiencing?

Somatic Experiencing is a body-oriented approach to treating trauma that focuses on processing traumatic memory, calming the nervous system, and releasing traumatic shock from the body.

Peter developed this approach by observing how animals behave in the wild. He noticed that, after being faced with a threat, animals are capable of returning to a regulated, healthy state relatively quickly.

Humans, on the other hand, tend to remain stuck in hyper-vigilance after experiencing trauma far more than animals do.

Peter concluded that this happens because moving out of a trauma response often involves coming back into contact with painful sensations.

For more primitive animals, this is a process they can’t resist. But as humans with higher-order thinking, we’re capable of avoiding those uncomfortable experiences.

The goal of Somatic Experiencing, therefore, is to help a client reconnect with their inherent ability to tolerate distressing emotions.

As Peter puts it,

“The basic idea is to guide people to help them recapture this natural resilience. And we do this through helping them become aware of body sensations. And as they become aware and able to befriend their body sensations, they are able to move out of these stuck places.”

– Peter Levine, PhD, What Resets Our Nervous System After Trauma?

So, what are some strategies from Somatic Experiencing that you might use when working with a client’s trauma? Here are just a few that Peter uses:

- Breathwork – This might involve having a client put one hand on their head, one on their chest, and then breathing into the hand for a few moments. Often, your client will eventually feel a shift, whether it’s in energy, temperature, or any other kind of change.

- Posture – Along with Pat Ogden, PhD, Peter emphasizes how posture can reflect a person’s mental state. Because of this, Peter will often have a client go into a hunched, “shamed” posture, and then slowly straighten their back to sit more upright. According to Peter, this exercise can help a client become more capable of talking about their shame.

- Noticing bodily sensations – This might involve asking a client to focus on where they feel stress in their body and to pay attention to its qualities. The goal here is to help your client get in better touch with their bodily states.

But why exactly is working with the body such a central aspect of Somatic Experiencing? Well, let’s take a step back – and let’s ask, how does trauma affect the brain and nervous system?

How Does Trauma Affect the Brain and Nervous System?

When faced with danger, our more primitive brain structures – the ones that are responsible for ensuring physical survival – get activated. And after the threat has passed, these are the areas of the brain that remain ruptured.

That’s why, rather than relying on more cognitive approaches that address the parts of the brain involved in critical thinking, Somatic Experiencing focuses on treating trauma using bottom-up strategies.

So, just like Bessel van der Kolk, MD and Pat Ogden, PhD, Peter emphasizes that effective trauma therapy often involves more than just verbal communication. In fact, Peter even acknowledges that sometimes, trauma can’t be verbalized.

Now of all the ways one might respond to threat or danger, Peter’s research has primarily focused on one specific trauma response – that is, the freeze response.

What is the Freeze Response?

The freeze response is one of the body’s involuntary defense responses to threats. Peter describes this response as, “an armor against an unacceptable feeling.”

While fight and flight are two strategies that are more commonly discussed in the field, freeze is an equally prevalent response. When fighting and fleeing aren’t possible, people will often go into freeze.

But what exactly does this response look like? Here are a few key signs that a person is in freeze:

- Tense muscles

- Heart rate increases

- Wide eyes

- Your client may say they feel “stuck” – or, be unable to speak at all

- Energy seems to be “locked up”

Now on the surface, some of these behaviors might seem like they’d be detrimental to a person. But to understand how they can actually be adaptive, consider this example . . .

Imagine a gazelle grazing on the Sahara . . .

From close behind, a lion stalks this prey. Suddenly, the gazelle notices it’s being followed. To protect itself, the gazelle freezes. Perplexed by this abnormal behavior, the lion loses interest in the gazelle and wanders off in search of other prey.

So as you can see, the gazelle was able to escape this predator thanks to its freeze response.

Now while this freezing can be adaptive in the moment, where it becomes harmful is when persists even after the threat has passed.

Think back to what we said earlier, about how after trauma, humans tend to stay stuck in their survival response.

As Peter puts it, this happens because humans are capable of resisting the uncomfortable emotions that can come along with moving out of a trauma response:

“The very sensations that will help take us out of the freeze response back into balance, those sensations are often frightening to a person. So they stop those sensations from happening, but it’s the very sensations that will take them out of the freeze response that they’re stopping.”

– Peter Levine, PhD

So, how can we support clients as they begin to come back into contact with distressing emotions?

How to Help Clients Reset Their Nervous System After Trauma

To help clients shift back into a more regulated state after trauma, Peter uses this nine-step method from Somatic Experiencing:

- Create a sense of safety – Before diving into any exercises or interventions, it’s crucial that your client feels safe. To do this, Peter says you can convey cues of safety via your social engagement system.

- Support your client as they begin to get in touch with their surroundings and the environment – Here, you want to encourage your client to briefly get in touch with their sensations, and then return to the present moment with you the practitioner.

- Encourage your client to stay with sensations, even if the experience feels uncomfortable – Peter points out how, as a client begins to get in touch with their bodily sensations, they’ll often feel discomfort initially. That’s because if trauma is stuck in a client’s body, they’ve often managed by avoiding their emotions. But even though it can be discomforting, learning to sit with uncomfortable emotions is an important step in healing from trauma. So, Peter makes a point to encourage clients to sit with those emotions – and he supports them as they do so. Through this process, clients can learn that uncomfortable emotions do pass – and that they’re capable of withstanding more than they may think.

- “Titrate” experiences for your client – This involves exposing your client to the smallest “drop” of arousing emotions and difficult sensations. Doing this allows your client’s nervous system to slowly build more stability and resilience, without retraumatizing them. This process involves oscillating or “pendulating,” as Peter calls it, between experiencing some distressing emotion and then returning to feeling safe and calm.

- Provide corrective experiences – This entails having your client feel and embody new, positive experiences that contradict the traumatic experiences they’ve had in the past. This can help reframe traumatic memories, rewrite the negative impact trauma left on their nervous system, and help them feel empowered.

- “Uncouple” fear from immobility – According to Peter, when a person starts to come out of immobilization, they’ll often experience dysregulating emotions. Because of this, they may associate immobilization with danger. Peter says that as practitioners, we can help clients undo that association by working with them to contain high-arousal emotions when they arise as they’re coming out of freeze.

- Help your client manage their arousal states – The goal of this step is to have your client shift from using all their energy to be on high guard, and instead use it for more higher functioning, positive behaviors.

- Help your client practice self-regulation – In this step, Peter says the goal isn’t to have clients’ emotional states always remain stable. Rather, self-regulation means being able to come back to a relaxed, balanced state even when a client becomes dysregulated.

- Help your client reorient to the “here and now” – At this point, your client will have the resources and skills to reestablish their capacity for social engagement.

Through this nine-step process, you can help your client release high levels of arousal, redevelop a sense of stability, and as Peter describes it, “transform trauma.”

References

For More Information . . .

Check out a course featuring Peter Levine, PhD:

How to Work with the Part of Trauma That Can’t Be Verbalized

Expert Strategies for Working with Traumatic Memory

2.75 CE/CME Credits Available

The Treating Trauma Master Series

10 CE/CME Credits Available

Working with the Pain of Abandonment

4.25 CE/CME Credits Available

Find out more about how Peter Levine, PhD works with trauma here:

When a Client Is Stuck in the Freeze Response

What triggers the freeze response? We tend to think . . .

One Common Mistake Practitioners Make That Can Heighten a Client’s Shame

Working with Traumatic Memory That’s Held in the Body

Our work often centers on our clients’ feelings and sensations . . .

Two Simple Techniques That Can Help Trauma Patients Feel Safe

One of trauma’s most insidious effects is . . .