Working with Anxiety

How can we help clients when anxiety takes over and their daily lives are driven by uncertainty and fear?

Most people, at some point in their lives, have experienced some feelings of anxiety.

After all, we are constantly trying to navigate life’s series of unknowns — unknown risks, unknown rewards, and unknown results. Of course, not all uncertainty leads to anxiety, but uncertainty does invite projection.

Now, when we believe we have the resources or coping skills to manage uncertainty, the anxiety is minimal, and we can go about our lives as usual.

But for clients who are predisposed to expect danger, and who continually underestimate their ability to cope with that danger, anxiety can surface at any turn.

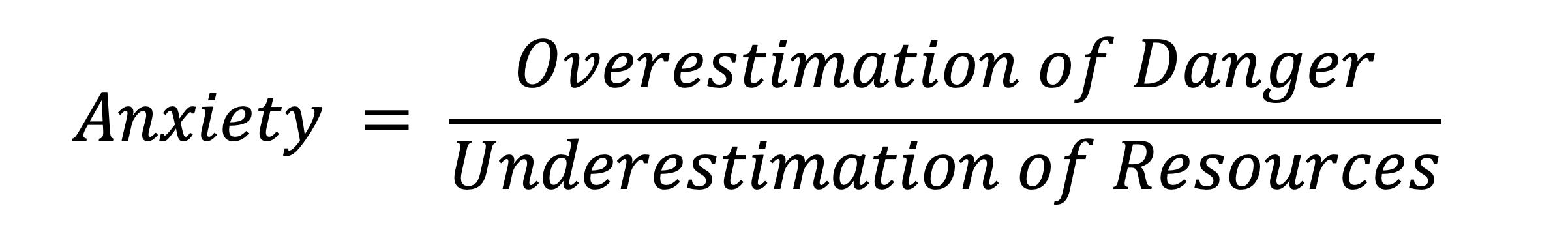

You see, anxiety can be summarized in a simple equation:

Root Causes of Anxiety

In order to better target our strategies for calming anxiety, we have to identify the roots.

Of course, there are many reasons a client might experience chronic anxiety, whether it be a genetic predisposition or a traumatic experience in the client’s history. But to fully understand the nature of anxiety, we have to look back much farther than the client’s personal experience. Because according to Ron Siegel, PsyD, the modern experience of anxiety is actually “an evolutionary accident.”

Think of an early human trying to survive out on the African Savannah.

Like most forms of life, this early human had several built-in survival mechanisms to help them pass along their DNA – namely, the fight/flight/freeze response.

Like most forms of life, this early human had several built-in survival mechanisms to help them pass along their DNA – namely, the fight/flight/freeze response.

But if this early human had come face-to-face with a lion armed only with fight/flight/freeze, chances are it wouldn’t have gone well. A lion would pursue much faster than they could flee, would be much too strong to fight off, and most likely wouldn’t be fooled by a lack of movement.

Another survival mechanism was absolutely necessary.

So early humans developed the ability to remember past experiences and project them to the future. That way, if they spotted a lion, they would remember the potential danger and wouldn’t go back to that place.

Now here’s where the problem lies. . .

Our capacity for thought, combined with the nervous system’s responses of fight/flight/freeze (plus other responses we’ve developed), work extremely well together for the purposes of survival.

But this often comes at the expense of our happiness. As Rick Hanson, PhD, describes, the mind is like Velcro for bad experience and Teflon for good ones.

In the face of uncertainty, it’s easy to feel at the mercy of whatever happens. That’s why anxiety can lead to cycles of rumination. Our brains treat worry as taking action, even though it actually disrupts the stream of rational thought.

On top of that, many clients with anxiety have been told that they are over-reacting or that it’s all in their head, which of course may perpetuate another anxiety about, “Something must be wrong with me.”

So providing psychoeducation about the evolutionary roots of anxiety may be useful in reducing some of that shame.

After all, anxiety feels bad because we’re supposed to want to relieve it — if we didn’t, it wouldn’t have been effective in getting us away from danger. It’s just doing its job a little too well.

How Mindfulness Can Help Clients Manage Anxiety

Mindfulness can be particularly powerful in helping clients disrupt fear and manage anxiety on a neurobiological level.

You see, there are two models for working with anxiety: decreasing the sense of danger, or increasing alternative resources and coping strategies. As one ancient metaphor puts it, we can either cover the world in leather, or we can put on a pair of shoes.

Of course, the ways in which we attempt to relieve anxiety can be problematic in themselves.

If you have children, or perhaps when you were a child yourself, you may have heard of “The Game.” It’s a vague mind exercise with a simple premise: if you think about it, you lose. There have been many variations of this game throughout history, but the result is always the same — the more we try not to think about something, the more it seems to infiltrate our thoughts.

Thought suppression is one of the most common ways people attempt to avoid their anxiety. There are even some therapies, and many advertisements for medications, which reinforce the idea that the goal of anxiety therapy is to get rid of the anxiety itself — but similar to how many children find themselves repeatedly losing “The Game,” often, the harder we pull away, the tighter it grips.

That’s why Ron Siegel, PsyD,[1] recommends helping clients embrace a different approach: mindfulness.

That’s why Ron Siegel, PsyD,[1] recommends helping clients embrace a different approach: mindfulness.

You see, when anxiety takes hold, the nervous system goes into a state of defense visible all the way down to a neurobiological level. So, the cues of danger make it to the amygdala and the limbic system, but there is a disruption in the signal before it reaches the prefrontal cortex, which would normally provide some downregulation.

But mindfulness can strengthen the integration between the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system because it helps to process all of our internal sensations on a higher level.

So what are some mindfulness techniques that can help to disrupt fear and manage anxiety?

- Labeling — Studies have shown that just naming an emotion can help bring the prefrontal cortex back online. By helping clients to name and embrace the sensations of fear and anxiety, we can tap into the brain’s natural regulation system, often bringing a client back into their window of tolerance.

- All Right, Right Now — Rick Hanson, PhD recommends one simple mindfulness technique in particular. As he points out, in most moments, we are basically alright. In the past there may have been moments where the body was actually in pain or danger — and there may be more in the future — but most often, we have enough air to breathe, there are no sharks biting off our legs, and the body is basically alright.

Just like how the body sends cues of pain or discomfort to the brain, it is constantly sending cues of being basically all right. But since we are in that state so often, we habituate to it. By helping a client develop a series of questions to re-engage that sense of being basically all right, they can use their body’s cues to ground themselves, even outside our office. And rather than push the anxious thoughts away, mindfulness techniques like this can help clients shift their focus and step out of the thought stream so they can experience anxiety as a passing phenomenon.

But there is an important caveat to beginning mindfulness work with a client. You see, if someone were to dive right in to mindful awareness of all the unrest in their mind, it would be easy for them to become suddenly overwhelmed at the magnitude of all they suppress — especially if their anxiety is rooted in trauma.

That’s why it’s so important to equip a client with other grounding strategies before beginning this kind of approach.

Body-Oriented Approaches to Working with Anxiety

As it turns out, recognizing and addressing the symptoms in the body may actually be the key to working with anxiety.

Take, for example, a client who struggles with anxiety about public speaking. Perhaps they have a big presentation coming up at work, but even rehearsing in front of the mirror can bring on nausea and hyperventilation.

What are some of the body-oriented approaches that may help calm their anxiety?

- Breathwork — Focusing on the breath is a common grounding strategy that’s used with both mindfulness and body-oriented approaches. It can often be easy to implement, and there are a variety of ways that clients can use it in their everyday lives. The client above, for example, might benefit from practicing “vooo breathing,” an exercise that Peter Levine, PhD teaches to many of his clients. But, as Joan Borysenko, PhD points out, some clients — especially those who struggle with perfectionism — might fear they’re doing the breathing exercises wrong, which can increase their anxiety. In that case, the client might adopt a strategy favored by Stephen Porges, PhD – adding more words to their phrases. Increasing the lengths of phrases naturally increases the length of each breath, which can act as an over-ride switch for calming the nervous system.

- Locating and Observing — It can be helpful for clients to focus on where in their body they feel the anxiety. If they can locate and isolate the anxiety, they can start to notice how that feeling changes as they begin to move back into their window of tolerance. Over time, as clients become more in-tune with their physiological reactions to anxiety, they can focus on them in a softer way that can help promote change.

- Posture — Of course, the breath isn’t the only part of the body we can work with to help reduce anxiety. According to Pat Ogden, PhD, posture can also be an important tool to reduce anxiety because the body’s posture often reflects the internal experience. Someone who is afraid of not belonging or being out of place is likely going to be hunched over on themselves, whereas someone who knows they belong might be willing to take up a little more space. By helping clients identify how their posture perpetuates or protects from their feelings, we can slowly make adjustments to increase a client’s confidence and help foster a sense of containment and safety.

The Specific Challenges of Social Anxiety

Social anxiety can be particularly challenging to treat because of its resistance to some of our most common strategies.

For example, when we think of anxiety, fears, and phobias,[2] one of the common ideas that comes up is exposure therapy.

Now, there are many opinions on exposure therapy itself, but many therapeutic techniques do use a small amount of exposure to help clients re-evaluate their sense of risk: behavioral experiments.

If a client were experiencing anxiety in the form of perfectionism, a small behavioral experiment may start by looking at where in life they already allow small imperfections, and widening the existing room for error. For example, if a client allows their kids to leave the house without making their beds, a small experiment might be to have the client run a short errand without making their own bed.

But when clients experience social anxiety, similar behavioral experiments may prove futile.

You see, many clients with social anxiety don’t fear that they will be publicly shamed, but rather that people will be too polite to verbalize their silent criticism. So although they may make it through a social interaction with nothing bad overtly happening, there is no way to examine the internal thoughts of others. Even direct, verbal reassurance can be doubted, simply perpetuating the anxiety.

So how can we help clients overcome the limitations of social anxiety?

One option is to have clients practice an assertive defense strategy.

Now, there are two extreme responses to criticism: passive acceptance, or anger and aggression. For example, if someone were to say, “You’re stupid,” a passive response might be to agree and internalize it, whereas an aggressive response would attack the perpetrator, “No, you’re stupid.”

Now, there are two extreme responses to criticism: passive acceptance, or anger and aggression. For example, if someone were to say, “You’re stupid,” a passive response might be to agree and internalize it, whereas an aggressive response would attack the perpetrator, “No, you’re stupid.”

An assertive defense response takes a middle-ground approach. In that situation, a client might respond, “Maybe what I did was stupid, but I am not inherently a stupid person.”

In many cases of social anxiety, the criticism isn’t given aloud, or may even simply be a projection, so there may not be an opportunity to verbalize the assertive defense in front of others. But even formulating such a response and saying it to oneself can disrupt the cycle of rumination.

Moving Forward with Anxious Clients

Anxiety doesn’t make life easy. But courage isn’t not feeling fear. It’s doing what’s meaningful anyway.

That’s why what you do is so important. By helping a client pursue their values despite the fear and anxiety, you impact not only their lives, but the lives of their community and the entire world.

References

Want more ideas and strategies you can use with your clients today?

To learn more about the latest strategies for working with anxiety, check out one of our courses:

Expert Strategies for Working with Anxiety

4 CE/CME Credits Available

Concrete Strategies to Help Clients Overcome Anxiety

3 CE/CME Credits Available

Working with the Fear of Rejection

3 CE/CME Credits Available

Expert Strategies for Working with Impostor Syndrome

3.25 CE/CME Credits Available