Treating Attachment Trauma

Early attachment traumas can have long-lasting effects on a client’s life – effects that are often subtle. So how can we recognize attachment trauma and set clients on the path to healing?

Let’s say a woman runs into a store and quickly grabs prepackaged sushi for lunch. In a rush to get to work, she doesn’t realize the expiration date on the sushi was several days ago. A few hours later, this woman feels nauseous and begins to vomit.

If you’ve ever had food poisoning, you’ll know that it isn’t an experience you’d like to repeat. In fact, it’s likely that this woman will avoid sushi for a long time, even if she knows it isn’t tainted, because even the smell can trigger memories of how sick she had gotten.

When someone has had an attachment rupture, especially in early childhood, it can be a lot like food poisoning.

What Is Attachment Trauma?

Attachment trauma refers to severe ruptures to attachment bonds, often in early childhood.

Take, for example, a young boy raised by a single mother. His father left when he was young, but his mother served as a strong support system for him. . . until they fell on hard times economically.

When she had to take on a second job to support them, she was no longer around as often to help him navigate life. When she was there, she was exhausted and emotionally drained.

The boy watched as neighbors and extended family offered to help, but his mother’s pride prevented her from accepting it.

Even without any intentional malice, the boy started to feel abandoned by his mother, his biggest source of support, compassion, and intimacy. In this way, the boy may have started to associate these positive traits with the shame, fear, and sense of danger.

Unfortunately for our clients, forming associations like this can cause the trauma to then be re-enacted throughout their lives.

How Attachment Trauma Lingers Later in Life

Attachment trauma in adults can be detected through defenses and coping mechanisms. You see, the coping mechanisms that once were adaptive for surviving this early attachment trauma can become maladaptive later in life.

But as Janina Fisher, PhD, says, “Nobody wakes up in the morning and says, ‘I’m going to go re-enact some trauma today.’”

Take, for example, the boy from before. He has grown into a successful businessman, and he now works in a large office. One evening, he is staying late to finish some paperwork when a colleague notices him, and offers to help.

Many of us would jump at such an offer. But based on the modelling of his mother and his own need to take care of himself as a child, this man actually finds the need for others to be contemptible. In fact, he gets offended at the offer, interpreting it as a comment on his capabilities rather than his workload. He may even get visibly angry, ultimately alienating a colleague who might otherwise have made for a great friend.

Many of us would jump at such an offer. But based on the modelling of his mother and his own need to take care of himself as a child, this man actually finds the need for others to be contemptible. In fact, he gets offended at the offer, interpreting it as a comment on his capabilities rather than his workload. He may even get visibly angry, ultimately alienating a colleague who might otherwise have made for a great friend.

Let’s say this man feels even more pressure to complete this work himself because there is the danger of impending layoffs at his company. When he finally goes home to his girlfriend, she notices his stress and asks him what’s wrong.

Now, as humans, we are wired to desire closeness when we don’t feel safe. It’s part of our biology. But for a client who has developed such an aversion to compassion and other cues of safety, that closeness can actually re-activate the threat system because they have learned not to trust safe. So rather than responding or taking the opportunity to vent to his girlfriend, this man shuts her down.

After some time of this pattern repeating, his girlfriend gets frustrated and leaves him, reinforcing this man’s narrative of abandonment. An unconscious reenactment of trauma.

Types of Attachment

As you may already know, attachment theory outlines four types of attachment that children develop based on their relationship with their caregivers. These attachment styles can influence a client’s relationships throughout their life, much like we saw in our example above.

The four major styles of attachment are:

- Secure Attachment – People who develop a secure attachment style had caregivers who were loving, caring, and readily available to respond to their needs as a child. People with secure attachment are able to engage in healthy, stable relationships with others.

- Avoidant Attachment – According to Dan Siegel, MD,[1] about 20% of people develop an avoidant attachment style. This style forms when a child’s needs were not met by their caregiver, so the child learned to meet those needs on their own. As the child grows older, they may avoid asking for help from friends or from teachers in school because they don’t think they need anyone’s assistance. Later in life, they may appear emotionally distant to romantic partners.

- Ambivalent Attachment – An ambivalent attachment style develops when a caregiver is inconsistent and unpredictable. Sometimes they’re there for the child, sometimes they’re not. Or, they may be overly intrusive at times, and extremely distant at others. This can leave a child insecure and unsure about how others will respond to them later in life. It may appear as clinginess in some cases, or mistrust in others.

- Disorganized Attachment – This style is most often associated with abuse and neglect, but that isn’t always the case. Clients with disorganized attachment did not have their feelings of distress addressed as a child and are often left with few or no resources to help regulate their emotions. Most relationships have a give and take aspect to them, but for clients with disorganized attachment, their relationships include almost all take and little to no give.

Applying Attachment Theory to Therapy

Attachment theory[2] can play a key role in identifying where to begin therapy.

For example, a therapist may recognize that the boy from our example has a disoriented or disorganized attachment style, or a confusing mix of avoidant and ambivalent-type behaviors. giving the therapist a clue where to begin their work. In this case, the boy’s attachment style was rooted in the mother’s caregiving nature coupled with her extended absences.

But attachment styles aren’t set in stone. People can learn secure attachment at any point in life — and that’s where therapy comes in.

Now, for clients who have never had a safe attachment figure, opening up to any human, even a therapist, may feel dangerous. But according to Ruth Lanius, PhD, it may help to have the client start by working with an animal.

If the client has a pet, such as a dog or cat, we might suggest they spend time with them, focusing on the feeling of its fur if they like to cuddle, or just the presence of this being in the same room. Through a mindful connection to the presence of this animal, the positive experience can begin to overwrite some of the fears associated with closeness to others.

If the client has a pet, such as a dog or cat, we might suggest they spend time with them, focusing on the feeling of its fur if they like to cuddle, or just the presence of this being in the same room. Through a mindful connection to the presence of this animal, the positive experience can begin to overwrite some of the fears associated with closeness to others.

Even if the client doesn’t have a pet, Ruth suggests that even the imagery of a favorite animal can begin to widen a client’s window of tolerance for connection.

The Role of Compassion in Healing Attachment Ruptures

Healing attachment ruptures requires first understanding what sits at the core of insecure attachment: shame.

According to Daniel Hill, PhD, shame begins when some undesirable part of the self is threatened to be exposed to others, and it often starts with a jolt of hyper-aroused fear. Now, fear is centered in the amygdala, which fully develops at about 8 months in the womb. So even before we are born, we are receptive to these powerful feelings of fear and shame.

In this way, the key to helping clients build secure attachment is not dissimilar to ways in which we would help them shift out of feelings of shame: compassion.

It’s clear that compassion can be a slippery slope for certain clients — especially those with a history of attachment trauma. But that doesn’t mean we should avoid compassion-focused therapy altogether. So while it may be difficult for these clients to accept compassion from others, the answer may lie in compassion for oneself.

It’s clear that compassion can be a slippery slope for certain clients — especially those with a history of attachment trauma. But that doesn’t mean we should avoid compassion-focused therapy altogether. So while it may be difficult for these clients to accept compassion from others, the answer may lie in compassion for oneself.

So how can we begin to introduce self-compassion into the treatment of attachment trauma?

- Labeling – We might begin by labeling the client’s feelings with whatever descriptors best fit their individual experience. Both in compassion-focused therapy and self-compassion-oriented techniques, there is a large emphasis on the concept of common humanity. Sometimes, even putting words to a feeling can be beneficial because if there is a word for it, that means someone else, at some point in time, experienced it too.

- Psychoeducation – It’s also important to provide some psychoeducation around the biological and evolutionary context of attachment, helping the client to cognitively understand that although they may be reenacting trauma, it’s not their fault.

- Compassionate Imagery – Then, we might move on to some compassionate imagery. Some clients may benefit from simply envisioning a compassionate color — whatever color that, to them, appears calm and non-threatening — and breathing into it. Other clients may require something more involved, such as compassionate space imagery. By creating a place in their mind where they have control over everything that is present, clients can evoke images to help them feel safe, content, and soothed.Of course, some clients may have difficulty knowing what does feel safe or soothing for them. In that case, before building the compassionate space, it may be beneficial to do an inventory – what might be a place that has your best intentions in mind? Is there a physical place you like to go, or a place you’ve always dreamed of?

- Compassionate Self or Compassionate Other Imagery – Finally, the client might practice compassionate self or compassionate other imagery. For those who have trouble trusting others, like many who have a history of attachment trauma, it may be more effective to focus on compassion coming from the self. So, we can help clients find the part of themselves that is wise, strong, can see the big picture, and is willing to stand up for themselves. It is important to remember that a client doesn’t have to actually embody or become their compassionate self, as long as they can access an image of what that part of them would be.

By helping a client mindfully access their internal strengths, such as self-reliance, and channel them into self-compassion practices, we can help them build a tolerance for feelings of compassion and safety in general, better preparing them for future interpersonal relationships.

How to Recognize Attachment Trauma

Attachment trauma can be difficult to recognize, sitting invisible or unremembered for years. So before we can help a client heal from attachment trauma, we must first be able to identify it.

Many people think of trauma as the result of an individual event, but oftentimes, especially in terms of attachment, this can take the form of a constant or repetitive stress. To go back to an earlier example with the young boy and his mother, we might consider the father leaving to be an individual event inciting the pain of abandonment, but the attachment rupture is likely more deeply rooted in the mother’s repeated neglect.

Now, a repeated stress can take either the form of an intrusive or violent trauma, such as abuse, or a passive trauma like neglect and abandonment. But with the latter, the signs can be much more subtle. In fact, many of our clients may not realize this is part of the problem.

So how can we screen our clients for attachment trauma?

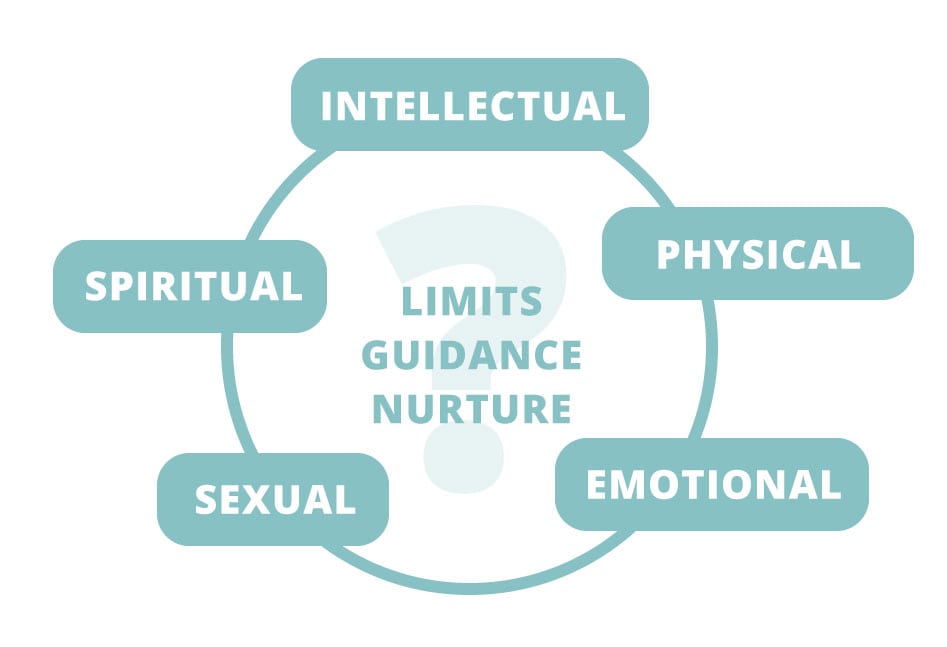

According to Terry Real, MSW, LICSW, the key is in asking about limits, guidance, and nurture in each of the five domains of human experience:

- Physical

- Intellectual

- Sexual

- Spiritual

- Emotional

But if a client is lacking nurturance in one of these areas, they may not be able to identify the lack because they don’t know anything different. That’s why it’s important to provide the client with examples. For instance, to understand if a client was nurtured physically, we should explore not only, “Was there food on the table? Did you have warm enough clothes?” but also, “How often were you hugged?” To get a sense of a client’s intellectual nurturance, you might ask, “Did your family all sit around at the dinner table and talk about ideas? Was somebody looking after your homework?” Or for emotional intimacy, “Who did you turn to when you had a fight with a friend? Who helped you when you were hurt, and how did they do that?”

Ruth Lanius, PhD, has another example of specific questions to get a sense of attachment history. She often starts with questions like, “If you could describe your mother in just a few words, what would they be?” or, “How would you describe your relationship with your father?”

Ruth Lanius, PhD, has another example of specific questions to get a sense of attachment history. She often starts with questions like, “If you could describe your mother in just a few words, what would they be?” or, “How would you describe your relationship with your father?”

Another important question Ruth suggests is, “Who did you feel safest with growing up?” Now, clients might be very complimentary to their primary caregiver, but still list someone else as who they felt safest with, indicating there might be a subtle attachment rupture. Or, some clients might say they’ve never felt safe with anyone, indicating their reluctance to trust or accept compassion may run deep.

No matter the severity of the attachment rupture, that trauma can continue impacting our client’s lives well into adulthood. But it’s never too late to heal.

And remember. . .

. . . when you help someone heal from trauma, you can change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References

Want more ideas and strategies you can use with your clients today?

To learn more about how to help clients heal from trauma, take a look at our courses:

Working with the Pain of Abandonment

4.25 CE/CME Credits Available

The Advanced Master Program on the Treatment of Trauma

12 CE/CME Credits Available

Master Series on the Clinical Application of Compassion

14 CE/CME Credits Available

The Neurobiology of Attachment

3 CE/CME Credits Available