Treating Trauma with Compassion-Based Therapies

Compassion can be uniquely effective for healing the shame and self-criticism that often stem from trauma. So how can we help clients begin to accept compassion – both from others and themselves?

Imagine, for a moment, an electrical fire has sent a house up in flames.

Thankfully, the family all made it out, but they are still agitated — their beloved cat is still trapped inside. When a team of firefighters arrive, the children beg and plead for them to save this cat.

Now, at this point, the fire is raging. It would clearly be dangerous to go inside the house, but one firefighter gears up and goes to find this cat. This doesn’t mean the firefighter is not afraid — in fact, she’s scared out of her mind. But she calls upon her training and goes to rescue the cat anyway.

Why would she do that?

Well, of course, it’s part of her job as a firefighter, but there’s something more than that, something that keeps her doing this job time and again: compassion.

Compassion is more than a feeling or a thought. It’s a motivation — and that’s part of what makes compassion-oriented therapies so effective.

Why Compassion is Critical for Healing Trauma

Compassion can impact clients on the level of both the mind and the body, making it effective in the treatment of a wide range of disorders – including some of the most challenging ones.

Let’s look at Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT) as an example.

You see, unlike many other schools of thought, CFT doesn’t stand alone. It is, as Dennis Tirch, PhD describes, “a modular therapy,” meaning it can be effectively used as a part of many other evidence-based therapy techniques, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).[1]

But before we can integrate specific compassion-oriented techniques into therapy, it’s important to understand the science behind its efficacy.

Now, when most people think of compassion, they often equate it with kindness or empathy. But while it may have elements of both in practice, compassion requires something more: an experience of suffering.

In essence, compassion serves as a stress response to suffering, and it happens in two stages:

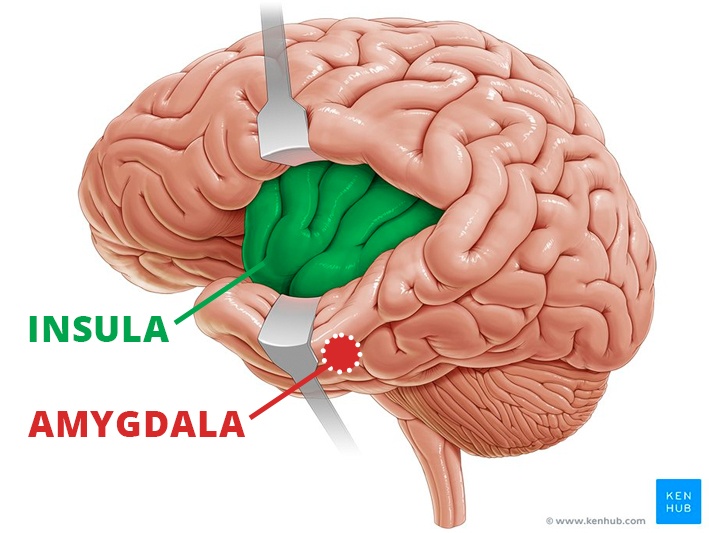

- Awareness – First, there is the initial awareness or recognition that something is wrong with the self or others. From a neurobiological perspective, this would involve the activation of the insula and the amygdala. There also needs to be some connection with the person who is suffering, whether that be a close relationship or simply the act of imagining oneself in their position.

- Activation – Then there is the activation, or the motivation to end the suffering. That’s when the prefrontal cortex comes in to strategize the best course of action.

Like the firefighter from our example, it often takes a deliberate act of courage to end suffering. One of the key side effects of compassion is that courage.

That’s because unlike many other stress responses, such as fight-or-flight, internal fear and panic are actually slowed down by a caregiving response — with a built-in rewards system. So by cultivating compassion, the brain will release more oxytocin and dopamine, associating the act of relieving suffering with positive emotion. In some cases, this can impact the consolidation of memory, reducing the lasting effects of trauma.

Compassion has also been shown to impact heart rate variability, enhance immune system functioning, and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression.

As Jack Kornfield, PhD, has found, it is easy to become overwhelmed by pain or suffering without compassion. But compassion practices allow people to widen their windows of tolerance and approach and navigate that which is difficult.

Trauma and Self-Compassion

Research shows that compassion-based therapies can be uniquely effective as a buffer against the harmful effects of trauma.

But how?

Well, to start, trauma can knock offline a person’s ability to develop self-compassion.[2] You’ve probably seen trauma survivors with a harsh inner critic or deep-seated feelings of shame.

Without intervention, those critical thoughts will continue to grow stronger, which can impact a client’s ability to manage stress and other difficult emotions.

But with compassion-based therapies, clinicians can resources clients with strategies to recognize when hostile thoughts creep in, and approach those thoughts from a gentler, more compassionate stance. That in turn increases a client’s tolerance for distress.

Not only that, but compassion-based interventions also help clients begin to accept compassion from others, which is something many trauma survivors struggle with.

A key part of treating trauma is helping clients heal relationships with those around them. But helping clients heal the relationship with themselves is just as important. That’s where compassion-based therapies offer such a unique avenue for the treatment of trauma.

Misconceptions About Compassion

Despite both the mental and physical benefits of practicing compassion, a few common misconceptions can serve as major roadblocks for clients.

For example, many people associate compassion with weakness, or they fear it will take away their competitive edge. Furthermore, people can often be even more resistant to the term “self-compassion,” believing it to be selfish or vulnerable.

In that case, Chris Irons, PhD, suggests going back to our initial story of the firefighter, asking the client for adjectives to describe that kind of person. Many people would say “brave,” “courageous,” or “strong.”

In that case, Chris Irons, PhD, suggests going back to our initial story of the firefighter, asking the client for adjectives to describe that kind of person. Many people would say “brave,” “courageous,” or “strong.”

Through some key psychoeducation about compassion as a threat response, and how it was necessary for the firefighter to rescue the cat, we can begin to shift client’s perceptions of compassion towards a more positive light.

But some people also believe it is a waste of time to do compassion practices in therapy — especially self-compassion — because they can do self-care on their own time. But self-compassion isn’t the same as self-care, and it certainly isn’t a do-it-yourself process.

You see, many cultures perpetuate the belief that when something is uncomfortable or painful, we need to get rid of it — often, through buying some sort of product or medication.

Compassion, on the other hand, guides us to acknowledge the hurt or discomfort. It’s much easier to turn to distractions like television or alcohol, so it’s a hard sell, and even harder for people to stay with it. And for some people, especially those who may not have had secure attachment in childhood, it can be particularly difficult to receive compassion, possibly even triggering a more harmful defensive response.

That’s why it’s so important to have a therapist or facilitator to guide the process — to help clients stay grounded in a healthy practice.

How Attachment History Can Impact a Client’s Openness to Compassion

When clients have not had a model of compassion throughout their attachment history, or have made negative associations with compassion, it can be particularly difficult for them to tolerate. Of course, compassion isn’t a one-way street. In fact, there are three major flows of compassion.

When clients have not had a model of compassion throughout their attachment history, or have made negative associations with compassion, it can be particularly difficult for them to tolerate. Of course, compassion isn’t a one-way street. In fact, there are three major flows of compassion.

- Compassion for Others – When we allow ourselves to feel compassion for others, the awareness of that experience can help expand our window of tolerance.

- Compassion from Others – When we recognize compassion from others and allow it to flow in, we are better able to coregulate and calm the nervous system.

- Self-Compassion – When compassion flows from the self to the self, we are providing support, care and understanding for ourselves in moments of distress.

Often, people aren’t equally receptive to each of these forms — and that brings us back to the very beginning.

You see, as humans, we aren’t independent from birth in the same way many creatures, such as lizards or snakes, might be. Instead, at the most fundamental moments in our lives, we rely on caregivers to meet our needs. It is through this demonstration by our primary caregivers which compassion is learned. But when our clients have experienced some early attachment rupture, compassion can quickly become associated with threat. And that makes it very difficult to receive compassion, either from others or the self.

Furthermore, when a client has had a deficit of compassion throughout their life, we might encounter another phenomenon: backdraft. You may have heard the term in reference to a fire — if the flames have exhausted the oxygen supply in a room, and someone opens the door, the rush of oxygen from outside will feed the fire, creating a sudden explosion. The same is true for compassion. When compassion enters a low-compassion environment, suddenly all the hurt parts of oneself which need the compassion will activate.

That’s why Jack Kornfield, PhD, believes that in therapy, it might be most effective to begin with cultivating compassion for others.

Through this exposure to the presence of compassion without the active threat of receiving it, we can help clients begin to widen their window of tolerance. That way, when we begin self-compassion practices, the vulnerability won’t be quite so overwhelming.

But there is another phenomenon we have to watch out for in compassion work: submissive compassion. According to Chris Irons, PhD, this can generally be equated with people-pleasing. So while it may look as though someone is acting in compassion for others, this response is not based in a legitimate caregiving instinct for the other person, but rather the fear of social rejection. And quite the opposite of genuine compassion, this is actually associated with higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. . . and a resistance to receiving compassion itself.

This can also be based in insecure attachment — but attachment styles aren’t set in stone, and people can learn compassion at any point in life.

Why Self-Compassion is Vital for Parents

When a parent practices compassion, they are teaching and modelling it for their children. But the importance of compassion in parenting goes beyond the flow to others in the family. In fact, some psychologists argue it’s actually more important for parents to have compassion for themselves.

Of course, parents often feel as though they cannot put themselves first. Like many people who struggle with compassion, they find it selfish or weak — especially since they understand another human being is dependent on them. But self-compassion isn’t necessarily putting oneself first. Rather, it’s recognizing that parenting is a hard job, and taking small steps towards making it more manageable.

According to Susan Pollak, MTS, EdD, helping a parent begin to accept the necessity for compassion often starts by helping them recognize the consequences if they don’t.

When anyone loses sleep, doesn’t have time for themselves, or is constantly interrupted and criticized, they are bound to get angry and irritable. And for parents, that can lead to fights with or heavy criticism of their children.

By taking the time to fulfill one’s own most basic needs, a lot of unnecessary suffering can be avoided.

How Compassion-Based Therapy Can Help Clients Manage an Inner Critic

Self-compassion is often necessary to help clients avoid giving in to the desire to be perfect – especially when they struggle with a harsh inner-critic.

Self-compassion is often necessary to help clients avoid giving in to the desire to be perfect – especially when they struggle with a harsh inner-critic.

Part of what perpetuates this critic is the belief that it is ultimately helpful — that despite the pain it causes, it protects us from further shame or harm. And this belief is often founded in past experiences, having helped a client navigate abuse or neglect.

But what was adaptive then isn’t always adaptive now, and an inner critic often leads to more harm than it protects from.

So how can we help clients cultivate self-compassion and manage their inner critic?

According to Deborah Lee, DClinPsy, it may be helpful to begin with a simple metaphor. . .

Imagine you have a child, and you are taking them to school for the first time. You have two options for teachers they might have: a critical teacher, and a compassionate teacher. Who would you choose? Why?

Now, most parents would prefer their child be taught by the compassionate teacher. In fact, if asked to go back in time as a child at school, most people would choose the compassionate teacher for themselves as well.

By helping clients see the benefits of the compassionate teacher, they can begin to question the necessity for their guiding inner voice to resemble the critical teacher.

Furthermore, Deborah suggests it can be helpful to question the critic’s credentials. Of course, people often automatically believe their own thoughts, however negative or intrusive they might be. By giving the client a way to externalize this critic, they can begin to look at what credentials they would like their guiding voice to have, and reject any thoughts from an underqualified critic.

How Compassion Can Ease Feelings of Shame

Deborah Lee also explains that compassion is extremely prosocial, meaning that it can help negate the feelings of not belonging that are associated with shame.

Of course, humans don’t feel shame for no reason — in fact, in small doses, it can be rather prosocial too. So when we’re working with shame, our goal isn’t to eliminate it completely, but to help client’s approach it in a more compassionate way. As Deborah says, “We feel shame because we are human, not because we are bad.”

Some key psychoeducation may be useful in helping clients to internalize this perspective. According to Paul Gilbert, PhD, there are three systems which help us regulate our emotions: the threat system, the drive system, and the soothing system. But when one system takes on more than the others, that can lead to dysregulation, self-criticism, and even shame — especially when the threat system takes over, leaving our clients in a constant state of defense.

Simply understanding the biological explanation for why someone reacts the way they do can take away a lot of the shame associated with it.

Moving Forward with a Compassion-Oriented Approach

There are many other compassion-oriented practices that may be beneficial for working with trauma, shame, an inner critic, and nearly every other aspect of a client’s life. But it’s important to remember that, as Jack Kornfield says, “It’s a practice, not a perfect. That’s why it’s called practice.”

There is no perfect way to help a client build a compassionate perspective, but gradually and inevitably, small practices will start to make lasting changes.

And remember. . .

. . . when you help someone heal from trauma, you can change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References

Want more ideas and strategies you can use with your clients today?

To learn more about compassion-focused therapy and its key practices, check out one of our courses:

Master Series on the Clinical Application of Compassion

14 CE/CME Credits Available

Integrating Compassion-Based Approaches into Trauma Treatment

3.25 CE/CME Credits Available

How to Work With Shame

4 CE/CME Credits Available

How to Work with Clients Who Struggle with an Inner Critic

4 CE/CME Credits Available