Working with Dissociation

Dissociation may be one of the more difficult and complex features of trauma treatment that practitioners face. So how can we more effectively identify and treat this challenging trauma response?

Most of us tend to think of the earth as solid. Of course, glaciers, rivers, and even human intervention can alter the landscape. On the surface, there are hills, valleys, oceans, but underneath it all, the earth is solid. . . right?

Well, if you’ve ever lived near a fault line, you’re probably familiar with the heart-stopping jolt of an earthquake beneath your feet.

You see, geoscientists have long since known that the earth’s crust is actually made up of several tectonic plates. And slowly but surely, each of these plates are moving.

According to Kathy Steele, MN, CS, humans are very similar.

There are many internal systems within the mind and body, and each is like a large plate that makes up the earth. But when our internal systems conflict, not unlike an earthquake, there’s a sort of tug-of-war – and something has to budge.

How to Identify Different Types of Dissociation

Research has identified several different types of dissociation that clients can experience.

Here are 5 different ways the mind may dissociate:

- Depersonalization – a disconnection from body and emotion, sometimes described as an “out-of-body” experience.

If a client were to look in the mirror and find their own face unfamiliar, they may be experiencing depersonalization.

- Derealization – a sense that the world isn’t real, as if seeing through a fog.

If a client describes colors appearing too bright, like in a badly edited movie, they may be experiencing derealization.

- Identity Disturbance – a sense of being a different person, or confusion about the self.

If a client who is morally opposed to drinking alcohol ends up doing so at a party and enjoying it, they may be experiencing an identity disturbance.

- Identity Alteration – a more extreme version of identity disturbance in which someone cannot control variation in personality or actions.

If a client reverts to a child-state without any conscious awareness of their adult self, they are likely experiencing identity alteration.

- Dissociative Amnesia – an extensive inability to recall important personal information or memories, sometimes referred to as “losing time.”

If a client was involved in a car accident but cannot remember why they were driving in the first place, they may be experiencing dissociative amnesia.

Clients may experience just one of these forms of dissociation, or any combination of them at various times. And of course, some parts may still be serving an adaptive function.

So, when working with a client’s dissociation, it’s important to find strategies that specifically address the part which the client finds problematic.

For example, if a client is frustrated by their tendency to lose time due to dissociative amnesia, Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD, suggests setting an alarm for a manageable amount of time for the client, be it 30 minutes or 3 hours, and having them write down whatever happened during that time frame.

By having the client go back and read through the previous entries, we can help them to significantly reduce lost time and stay grounded in the present throughout the day.

Is Dissociation an Adaptive Defense Response?

In many situations, the mind’s ability to dissociate is an adaptive – and rather heroic – response to trauma.

Take, for example, chronic abuse. By dissociating, the client is allowing the mind to leave, even when the body is trapped. As Stephen Porges, PhD, explains, “This act of dissociation has this wonderful function of preserving the individual sense of self while not corrupting it by the acts that are being perpetrated on the body.”

Polyvagal theory would describe dissociation as a dorsal vagal reaction. It may actually start off very similar to a death-feigning collapse response, but rather than limiting bodily function, dissociation allows the body to continue receiving enough oxygen, focusing the shutdown on the neural circuits instead.

Working with Dissociation as a Threat Response

Now, dissociation[1] is one of the nervous system’s many autonomic responses to threat.

Now, dissociation[1] is one of the nervous system’s many autonomic responses to threat.

And as you know, therapy often requires working with the parts of clients that feel most vulnerable and hurt. So even when we slowly build up to addressing these parts, even the mention of them can feel threatening.

The more dissociation has proven to be adaptive for clients in the past, the lower their threshold becomes, meaning they are more likely to start dissociating even in the face of smaller threats. But it doesn’t necessarily override the body’s other defenses.

You see, according to Kathy Steele, MN, CS, there may be a powerful connection between dissociation and each of the other defense responses.

Let’s start, for example, with the freeze response.

Freeze is a full-body response. So, if a dissociative client has one part that begins to freeze, the whole body will follow.

But dissociative parts have also developed protectors against pieces of the self. So, when a hurt or exiled part is triggered or begins to surface, protector parts may react with freeze to the anticipation of shame.

When this happens, it can seem – even to the client – that they have frozen out of nowhere.

So how can we work with this combination of freeze and dissociation?

- Grounding – Like with any threat response, it’s near impossible to continue therapeutic work in a state of defense. By using grounding strategies such as, we can help clients return to their window of tolerance.

- Backtracking – It’s important to find where the freeze response originated, both to avoid triggering it again and to begin to heal that hurt part. So notice, what was happening when the client began to freeze? Was it a response to fear or shame? It can be helpful to directly ask the client, “What were you aware of? What did that experience remind you of?”

- Parts Work – Then, we need to figure out the specifics. Was this response just one part reacting, or multiple? Of course, as Kathy points out, clients may not be immediately receptive to the parts model, and addressing them directly could trigger more fear or shame.

But often, given the opportunity to describe their experience, clients will, in a way, bring up their parts themselves. For example, if a woman processing attachment trauma freezes during a session, she might describe, “Well, a part of me felt like that little girl standing there, watching my parents fight.”

At that point, we can start to open the question, “So, do you feel frozen, or does the little girl feel frozen? How is that for you?”

- Psychoeducation – Once we have identified the parts where the response originated, we can use psychoeducation to explain how these parts were created, and why they were adaptive to have. This can help to reduce the shame around the response, and to initiate further parts work.

For example, you might ask the client if it’s okay to speak to a specific part, and if they say yes, address the protector part first.

By getting permission from the protector part to speak to the exiled, hurt part, we can avoid retriggering a defense response and instead get to the heart of our work.

The Structural Dissociation Model

Kathy Steele, MN, CS,[2] along with her colleagues Onno van der Hart, PhD, and Ellert Nijenhuis, PhD, built this structural dissociation model based on the “fault line” between the attachment system and the defense system.

Kathy Steele, MN, CS,[2] along with her colleagues Onno van der Hart, PhD, and Ellert Nijenhuis, PhD, built this structural dissociation model based on the “fault line” between the attachment system and the defense system.

Now, defense and attachment are both motivational systems, but they have fundamentally opposing goals: attachment drives us closer to something, and defense keeps us away. As such, they are biologically incompatible to have activated at the same time.

That’s where structural dissociation comes in.

Let’s think, for a moment, about a client with a disorganized attachment history. Perhaps this is a boy whose mother was loving but rarely around, or his father gave him his basic needs but was verbally abusive.

As a child, this client was reliant on his caregiver, and was therefore motivated by the attachment system to get closer. But at the same time, the caregiver’s inconsistency, abuse, or abandonment pose a threat, activating the defense system to protect against this same person. So, the systems conflict.

As a result, the child is left with a dysregulated nervous system. And to reconcile, the mind splits into dissociated parts.

Screening for Dissociative Identity Disorder

An accurate diagnosis can be important for effective treatment – so how can we screen clients for dissociative disorders?

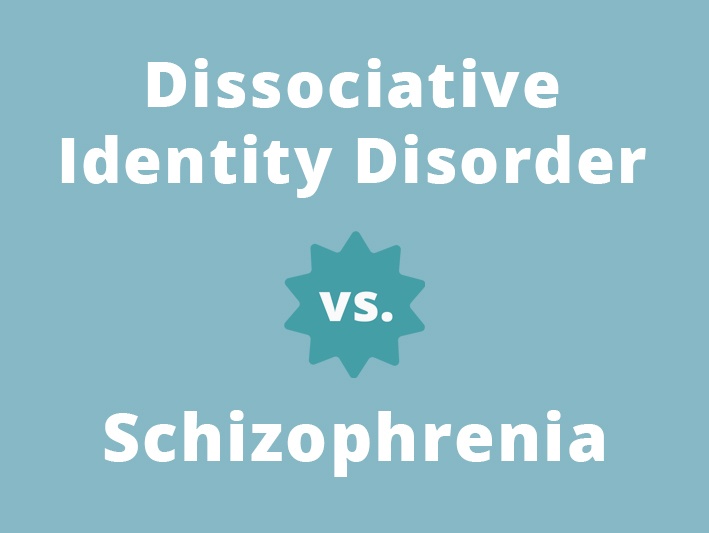

Bethany Brand, PhD, suggests that for a client to be accurately diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder (DID), they likely experience all five types of dissociation. But Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD, has another question which can help distinguish between dissociation and DID:

Do you ever hear voices?

Do you ever hear voices?

According to Bethany, more than 70% of clients facing DID do hear voices. But many people, including clients, automatically associate hearing voices with schizophrenia or other psychosis. . . and are therefore more likely to withhold information about their symptoms.

That’s why it’s so important to know the difference between presentations of DID and schizophrenia, and to provide some psychoeducation throughout the screening process.

So how can we differentiate between DID and schizophrenia?

- Cause – There are still many mysteries surrounding the causes of both schizophrenia and dissociative identity disorder; however, experts have found that dissociative disorders tend to be highly associated with trauma, whereas schizophrenia may have genetic factors.

- Onset – The age at which a client begins to experience symptoms may be a strong indicator. DID tends to manifest soon after trauma, often in childhood, whereas symptoms of schizophrenia don’t usually appear until a client is in their late 20s/early 30s.

- Number of Voices – According to Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD, clients with schizophrenia rarely hear more than 3 distinct voices. So, if a client hears many different voices, especially if they also have a history of multiple traumas, it is more likely that they are experiencing a dissociative disorder.

- Age of Voices – Ruth also suggests that child voices are common among dissociative disorders because they tend to be rooted in a childhood trauma. Clients with schizophrenia, on the other hand, rarely hear the voices of children.

Unfortunately, these indicators aren’t an exact science, but they can be useful in helping us to correctly diagnose clients.

You see, in many ways, diagnoses can be healing – they provide an explanation that may reduce shame and allow clients to feel a sense of common humanity with others who have experienced the same thing.

Not to mention, an accurate diagnosis may lead to more effective, targeted treatments. After all, the antipsychotic medications that may help someone with schizophrenia won’t do much to help clients process the underlying trauma that’s driving a dissociative disorder.

Moving Forward with Treatment

Treating a client who dissociates can be a difficult, sometimes even disorienting, process for practitioners. So it’s important to remember that when working with dissociation, patience can be key.

And remember. . .

. . . when you help someone heal from trauma, you can change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References

Want more ideas and strategies you can use with your clients today?

To learn more about how to work with a client who dissociates, check out the following courses:

Advanced Master Program on the Treatment of Trauma

12 CE/CME Credits Available

The Neurobiology of Trauma

3 CE/CME Credits Available

Treating Trauma Master Series”

10 CE/CME Credits Available

Working with the Pain of Abandonment

4.25 CE/CME Credits Available