How to Overcome the Freeze Response

The freeze response is complicated and nuanced – one small trigger can send a person into a state of complete immobility. So, how can we work with the freeze response more skillfully in a session?

Picture this . . .

You’re in a session with a client, and everything seems to be going smoothly. But then, you mention your client’s mother – the one who used to frequently hit your client when she was a young girl – and suddenly . . .

. . . your client stops responding. She sits there motionless, her gaze averted and locked on a painting in the corner of your office.

With the room now silent, you can hear her breath is rapid and shallow. And it’s subtle, but you notice her jaw clenching ever so subtly.

What’s going on with your client? Well, there’s a good chance she may have just gone into freeze.

What is the Freeze Response?

Freeze is one of several defense responses to trauma.

While the survival strategies fight and flight are more well-known, the freeze response has become increasingly identified and worked with over the past several years.

You see, if a person can’t flee or if fighting is ineffective, then they may go into a state of paralysis.

Many times, we see freeze in response to childhood trauma. Take our client from earlier, for example . . .

As a child, she would seek comfort and closeness from an attachment figure, like her mother. But the physical abuse she experienced at the hand of her mother would also trigger a fight or flight defensive response in her.

As a child, she would seek comfort and closeness from an attachment figure, like her mother. But the physical abuse she experienced at the hand of her mother would also trigger a fight or flight defensive response in her.

Because these two systems – the attachment system and the defensive system – are at odds with each other, the child doesn’t know what to do. And so instead, she might go into freeze.

Now in talking or reading about freeze, you may encounter a number of other terms – like tonic immobility, death feigning, and orienting phase, just to name a few.

Those terms describe several experiences that are similar to or related to freeze, each with their own nuance.

Now these terms are often interpreted differently across experts in the field. But here’s one way you might conceptualize them, according to Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD:

- Orienting Freeze – This is the state a person might go into when they’re first faced with a threat and simply trying to detect it. You might think of this orienting freeze as your initial response when you hear brakes squeal or a siren blaring, when you’re thinking, “Where’s this sound coming from, and am I in its path?”

- Tonic immobility – This refers to the rigidity of specific muscles, particularly ones that help us maintain our posture and help us breathe. From an evolutionary standpoint, this response can aid in survival by helping an animal blend in with its surroundings and hide from a predator. It’s one of several signs that a person is in freeze.

- Death feigning– Another term to describe the type of freeze we’re going to cover in this article, according to experts like Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD.[1] However, keep in mind that some experts, like Stephen Porges, PhD, and Pat Ogden, PhD, use the term “death feigning” or “feigned death” to describe another trauma response, one called collapse/shutdown.

So keeping all this in mind, let’s focus on what many experts simply refer to as the freeze response . . .

What Are the Key Signs of the Freeze Response?

These are a few signs of freeze that can be important to look out for in a session:

- Hyper-Alertness

- Increased heart rate

- Tension in the body and muscles (tonic immobility)

- Energy seems built up, but cant be released

- Some, but minimal verbal cues – like “I feel stuck,” “I can’t move,” or “I’m paralyzed.” Or, no speech at all.

- Shallow and rapid breath

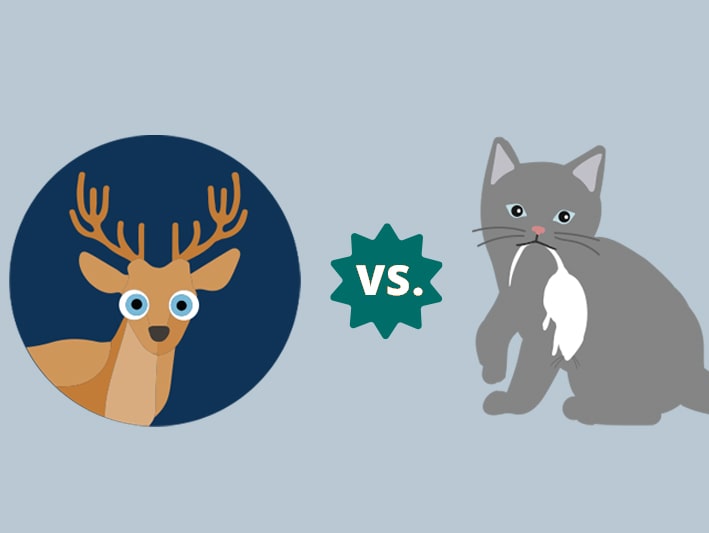

Now these signs may seem clear, but in practice they might not be so straightforward. That’s because the freeze response can look awfully similar to another type of trauma response: collapse, also known as shutdown.

Now these signs may seem clear, but in practice they might not be so straightforward. That’s because the freeze response can look awfully similar to another type of trauma response: collapse, also known as shutdown.

But here’s the thing: there are several key differences between collapse/shutdown and freeze.

Collapse/shutdown occurs when a person leaves their window of tolerance and goes into hypoarousal. It’s characterized by flaccid and loose muscles, a blank stare, and decreased heart rate.

On the other hand, something very different is happening in the nervous system when a person goes into freeze . . .

What’s Happening in the Nervous System When a Person Goes into Freeze?

Just like fight and flight, the freeze response is a form of hyperarousal.

Now when we’re dysregulated – whether that be in hyper or hypoarousal – our prefrontal cortex – which allows us to think critically – goes offline, while our limbic system – which drives survival behavior by responding to threat with vehement emotion – takes over.

What this means is that any information going into the brain – sensations, words, movements – can’t be processed in a logical, cognitive way.

At first glance, this may seem maladaptive, but think about it this way: If a person is experiencing a threat – whether real, or just perceived – immobilization can help them stay safe.[2] The limbic system is screaming, “Don’t move – or else you’ll die!”

So in many ways, freeze is actually a rather ingenious survival strategy.

Now all this may not seem immediately relevant to your clients, but here’s the thing . . .

Many times, when a client goes into freeze, they might look back at the event and think, “I should’ve fought back.” They might ruminate on what they could’ve done differently and ultimately blame themselves for what happened.

But by providing psychoeducation about the nervous system and how it reacts to trauma, you can help your client understand that, like all trauma responses, freeze is an involuntary response.

It’s not a conscious choice – it’s something that the body instinctively does to protect itself.

By sharing this with your client, you can help shift their attention away from wondering, “Why did this happen to me?” to being curious about, “Why did my body go into freeze?”

Through this exploration, they can discover that freeze – just like all trauma responses – is a normal, evolutionary response. It can help them gain awareness of the fact that freezing helped them survive in the face of trauma.

And this can help dissolve any shame and self-blame that might come with having responded to a traumatic event with freeze.

How to Help Clients Overcome the Freeze Response in a Session

One of the most important things to know when it comes to freeze is that when a client is stuck in this trauma response, they won’t be able to process verbal communication well.

That’s because, as we mentioned earlier, our prefrontal cortex – the brain structure that integrates verbal information – is offline when in freeze.

As Bessel van der Kolk, MD, says, “You cannot do psychotherapy or psychoeducation when people are frozen, because when you’re frozen, nothing can come into your brain until the frozenness is stopped.”

This is why, when helping a client overcome the freeze response, relying on words alone can often fall short.

Instead, because freeze paralyzes the body, we’re often better off treating freeze with a somatic or bottom-up approach.

Here’s a step-by-step approach you might take to help your client overcome the freeze response:

- Ask your client to nod their head “yes” or “no”– When working with freeze, it’s important to have clients start with small movements, like nodding their head back and forth. However, some clients might be so deep in freeze that they struggle to make these movements. In such cases, you might ask your client for an even smaller movement – for example, having them look to one corner of the room with their eyes with their eyes.

- Breathing exercises– Having clients take slow, deep exhalations can help activate the parasympathetic nervous system – that’s the system responsible for helping the body “rest and digest.”

- Have your client observe their surroundings intently – Once a client’s freeze has begun to “thaw,” you might encourage them to observe their surroundings in more detail. You might ask them, “Can you look around the room?” or “Describe three things in full detail.”

- Full-body mobilization – Having your client stand up and move around the room can help loosen their muscles, reconnect them with their surroundings, and get the body-brain connection back online.

- Co-regulate with your client– According to Polyvagal Theory, humans communicate with each other via their social engagement systems – or our vocal intonation and facial expressions. So by using calm prosody and inviting body language, we can impart cues of safety that help clients feel stabilized by our presence. You might think of this as “two nervous systems talking to each other.”

That said, there are some important cautions that come with working with the freeze response . . .

What NOT to do When a Person is Stuck in Freeze

When working with freeze – and trauma in general – it’s just as important to know what NOT to do as it is to know what TO do.

So as we’d expect, there are several “don’ts” that we need to keep in mind when we’re working with someone who’s in freeze.

If a client goes into freeze in a session, it’s important that we . . .

- Avoid making eye contact– To someone who’s experienced trauma and who is stuck in freeze, the proximity of eye-contact can be too intrusive and can further dysregulate them.

- Don’t offer touch. – If someone is frozen and unable to physically or verbally respond, unsolicited touch may feel violating.

- Make sure to ask for permission.– A core element of trauma is that it strips people of choice and control. This is especially relevant to clients who go into freeze – think about if a person frequently immobilizes in the face of danger; it’s possible that a perpetrator continued to harm them when the client was in that state. This is why respecting boundaries is essential when working with these clients.

- Work at a slow, gentle pace– Failing to do this could further dysregulate your client, potentially sending them into collapse/shutdown or dissociation.

- Don’t mistake a loss of speech for unwillingness to speak– If a client suddenly goes mute, this might seem like stubbornness, resistance, or a lack of cooperation. In reality, it might indicate that your client is involuntary stuck in freeze.

- Stay away from trying to “convince the nervous system” that it’s safe.– Because the prefrontal cortex is offline during freeze, verbally reassuring a client that they’re safe in a session won’t reach them – it and can actually be contraindicated. Instead, focus on imparting those cues of safety we mentioned earlier. As you probably learned in your elementary school writing classes, show, don’t tell. That said . . .

- Keep affective expression to a minimum– For many trauma survivors, positive emotion might actually be associated with threat. For instance, think back to our client from the beginning of this article. Her mother might’ve been loving and caring towards her one minute, but abusive and violent toward her the next. That child’s nervous system might remember that, “feeling good isn’t safe.” So, when we’re working to co-regulate with a client, we want to be gentle, warm, and inviting – but not overly engaging, animated, or empathetic, as this could be overwhelming.

- Make it clear that going into freeze is NOT a negative thing!– Remind your client that bodily responses to trauma are involuntary and a matter of survival – they don’t reflect a person’s strength, or lack thereof.

Helping clients come out of the freeze response requires great care and delicacy –the work isn’t always easy. But it’s important work to do, because the impacts can be far-reaching.

I believe that when you help someone heal from trauma, you change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References