Limbic System Therapy

For many clients, trauma lives on in the body and mind long after the event is over. So how can we target the limbic system to help clients heal from trauma?

Think, for a moment, about a dog in a thunderstorm.

If you’ve ever had a dog, you may be familiar with some of the common behaviors – frantic pacing, hiding under furniture, aggressive barking, or even biting at someone who gets too close.

In fact, you may have noticed that dogs begin these fear responses long before you ever hear the first clap of thunder. They have much more sensitive hearing and can recognize the storm from farther away.

When a client has experienced trauma, it can be like having a dog’s extra-powerful senses for danger.

But according to Bessel van der Kolk, MD, “To really overcome trauma, you need to take care of that ‘frightened dog’ inside.” And that means taking care of the limbic system.

What is the Limbic System?

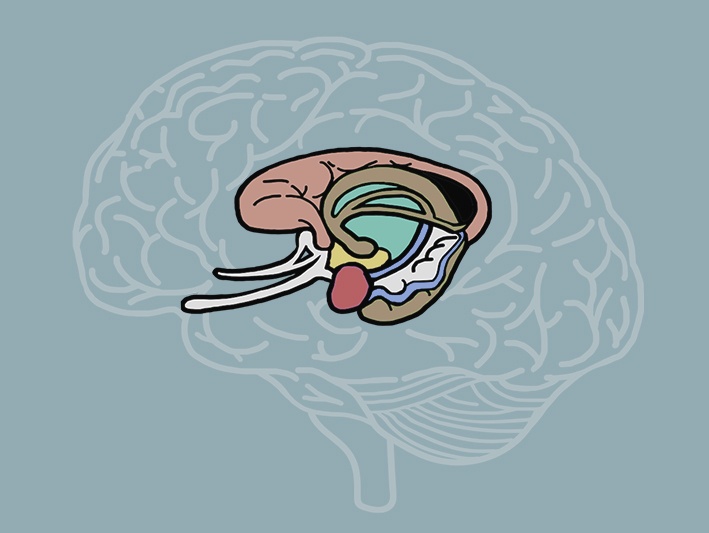

Sometimes known as the emotional part of the brain, the limbic system is a group of structures[1] which handle motivation, emotional response, and defensive systems.

The two largest structures of the limbic system are the hippocampus, which processes and stores memory, and the amygdala, which detects threat and responds emotionally.

The two largest structures of the limbic system are the hippocampus, which processes and stores memory, and the amygdala, which detects threat and responds emotionally.

Altogether, this system responds like our example of the frightened dog in the thunderstorm.

There is some question about whether it is neurobiologically useful to think about these parts of the brain as a unified system. But when it comes to therapy, the limbic system informs some of the most effective strategies for trauma treatment.

After all, according to Bessel van der Kolk, MD, trauma doesn’t live in the part of the brain that’s concerned with reason and insight. It inhabits an underlying understanding of the world, and the emotions and automatic defenses that accompany it. So, it only makes sense to target the parts of the brain behaving automatically.

Limbic System Therapy in the Brain

When we think about targeting the limbic system, we’re really looking at therapies focused on the midbrain.

But in addition to the amygdala and hypothalamus, Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD, emphasizes another structure in the limbic system: the periaqueductal gray. This part of the midbrain controls heart rate, blood pressure, and autonomic processes like pain reduction. So, it is highly active in the majority of human defense responses.

The periaqueductal gray also connects directly to the fusiform gyrus – a key structure in helping us recognize faces. That means we take many of our cues of danger from other’s facial expressions.

For example, according to Linda Graham, MFT, “Simply by making eye contact with someone who is calm, we can regulate our own body and nervous system to be calm.”

That’s just one example of how therapies which target the limbic system can work from the bottom up. The entire brain is connected, so by reorganizing the lower parts of the brain, we can actually reorganize the entire system.

Body-Oriented Strategies for Treating Trauma

One of the key insights the limbic system provides is the importance of working with the body in the treatment of trauma.

You may already be familiar with how traumatic memory can be encoded in the body and nervous system. But as Pat Ogden, PhD, points out, “Talk therapy might not have that hoped-for trickle-down effect to the subcortical brain where the responses to trauma in the body can be resolved.”

So, the body remains disposed to detect and respond to threats.

That’s why Bessel van der Kolk, MD,[2] suggests that we need to create “experiences which directly contradict how the body is disposed.”

Here are three examples of how we can use the body to treat trauma:

-

Posture

-

Movement

-

Touch

Peter Levine, PhD, once said, “Posture is really the story of the person’s whole life. It is telling you where a person’s life got stuck.”

So how can we use a client’s posture to help them move forward?

According to Pat Ogden, PhD, posture can influence a client’s emotional experience.

Take, for example, a client who is slumped back in their chair and quietly says, “I feel so empty.” If we coach that client to sit up straight, keep their feet planted, and say the same statement, they often automatically say it a bit louder. That’s because an upright posture is associated with confidence.

Take, for example, a client who is slumped back in their chair and quietly says, “I feel so empty.” If we coach that client to sit up straight, keep their feet planted, and say the same statement, they often automatically say it a bit louder. That’s because an upright posture is associated with confidence.

By having a client mindfully test different postures and report their emotional experience with each, we can use them to better help them stay grounded in their window of tolerance.

Christine Padesky, PhD, also emphasizes the importance of the practitioner’s posture during therapy.

When discussing something so intensely painful like trauma, direct eye contact can increase the intensity of those feelings, or may even feel threatening, causing the client to shut down. That’s why Christine recommends what she calls, “shoulder-to-shoulder” work.

You see, eye contact can be an important tool for showing that you are invested and paying attention. But cues like leaning forward can achieve the same goal with less intensity.

So, by moving a chair to sit at an angle to the client, or possibly even side by side, we can reduce the sense of obligation for eye contact while maintaining the therapeutic relationship.

Bessel van der Kolk, MD, has said, “Trauma is all about being unable to move and being helpless. So, in order to become a capable person, you need to learn to move and to get what you need.”

Bessel van der Kolk, MD, has said, “Trauma is all about being unable to move and being helpless. So, in order to become a capable person, you need to learn to move and to get what you need.”

Experts such as Joan Borysenko, PhD, Pat Ogden, PhD, and Bessel van der Kolk, MD, have suggested practices like:

Bessel has even found that, “Yoga is more effective than any medication that has ever been studied for PTSD.”

But not all types of movement are so effective.

In the 1960s, catharsis was regarded as a widely accepted trauma treatment. Clients would scream and beat pillows. But as many body-oriented therapists would critique now, this doesn’t integrate the brain.

You see, trauma can shut down the regions of the brain associated with critical thinking, leaving the more primal, impulse-driven parts of the brain in control. In effective therapy, we help those impulsive parts re-start communication with the regions capable of critical thinking. But with catharsis, as Pat Ogden, PhD, explains, “That person is dissociating into just that part of themselves. They’re playing out their subcortical impulses, but it’s not integrated with the cortex.”

And left uncorrected, this dissociation can actually reinforce the client’s responses.

But there is a way to alter even the catharsis strategy to be an effective movement practice. By having the client simply report back what they are feeling as they complete these striking motions, we can introduce some stimulation for the prefrontal cortex, integrating the mind.

Touch is one of the primary mechanisms of soothing. Let’s think back to our first example of the dog in the thunderstorm . . .

Now, many people think of petting a dog as a comforting activity for them, but it actually works both ways.

After all, in addition to all the defensive behaviors we discussed before, many dogs seek out their humans during a storm – and they often calm down after being pet.

That’s because, as Joan Borysenko, PhD, explains, touch stimulates activity in the vagus nerve and calms the HPA axis.

With proper consent from a client, a light touch of the hand or a gentle squeeze may be helpful in calming the nervous system and grounding them in the present. But for some clients, it may be best to start with simulated touch, such as having them pet a soft blanket or wear a belt around their waist like a hug.

How to Approach a Client’s Trauma Story

As you can see, limbic system therapies don’t place much emphasis on the narrative aspects of a client’s story.

In fact, Bessel van der Kolk, MD, has even said, “At some point, the story often becomes an alibi. For many traumatized people, they tell the same story over and over again. Instead of feeling things very deeply, they go through a recital of misery, which is not the same thing as psychotherapy.”

In fact, Bessel van der Kolk, MD, has even said, “At some point, the story often becomes an alibi. For many traumatized people, they tell the same story over and over again. Instead of feeling things very deeply, they go through a recital of misery, which is not the same thing as psychotherapy.”

But that doesn’t mean we should ignore the narrative altogether. After all, as Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD says, “No trauma therapy is complete without really addressing brain, mind, and body , and really connecting all three.”

So, in trauma treatment, the client’s narrative still serves two key purposes:

-

Enhancing the Therapeutic Relationship

-

Naming and Taming the Experience

The therapeutic relationship can be vital in helping clients rebuild secure attachment and a sense of safety after trauma. But before clients can open themselves to the benefits of nervous system-to-nervous system communication, they often need a more concrete way of establishing trust.

That’s where the client’s trauma story comes in.

As Pat Ogden, PhD, explains, “Patients often need to tell their story to you, and they need to know that you can handle it, that you’re not going to freak out along with them.”

By demonstrating a calm yet empathetic response to the parts of their story that a client is willing to share, you can reassure clients that your office is a safe place to be vulnerable.

Furthermore, the verbal narrative can help you track hidden cues in the body. For instance, when a client’s posture contradicts what they’re verbalizing, that can indicate that there’s a deeper trauma to work with – and that it might need to be approached more slowly.

According to Chris Willard, PsyD, simply naming an emotional experience can help clients “tame it,” or regain a sense of control.

That’s because when someone is exposed to an emotional stimulus, the amygdala lights up, activating the limbic system. But by naming an emotion, the client activates their prefrontal cortex. According to Tara Brach, PhD, this creates a top-down feedback system – the cortex informs the limbic system of what emotions are needed and appropriate, lessening the power of the emotions to overstep their bounds.

But as Bessel van der Kolk, MD, clarifies, the impact of “naming and taming” trauma also depends on how much secrecy there is about the event.

Take, for example, a car accident. Perhaps it was icy, and a large deer came out of nowhere. In a case like this, there are no secrets. We all know how an accident like that may happen. There is no blame involved, and there’s less of an emotional stimulus. So, retelling the story isn’t going to be inherently helpful.

On the other hand, imagine a client who grew up in an abusive household. Childhood loyalty toward caregivers has prevented this client from telling the truth for years, or maybe even decades. So, in this case, being able to say what really happened and finding words for what that child was experiencing can be incredibly powerful.

Moving Forward with Limbic System Therapy

As Bessel van der Kolk, MD, explains with his clients, “Rather than saying, ‘Tell me more,’ I say, ‘So where do you notice it in your body? And what comes up when you pay attention to that?’”

By targeting the limbic system like this, we can help clients integrate their brain, mind, and body and begin to heal after trauma.

And remember. . .

. . . when you help someone heal from trauma, you can change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References

Want more ideas and strategies you can use with your clients today?

To learn more about how to work with trauma at the level of the nervous system, check out some of our courses:

The Advanced Master Program on the Treatment of Trauma

12 CE/CME Credits Available

The Neurobiology of Trauma

3 CE/CME Credits Available

Target the Limbic System to Reverse Trauma’s Physiological Imprint

3.25 CE/CME Credits Available

Treating Trauma Master Series

10 CE/CME Credits Available