How to Overcome Shame

At some point in life, almost everyone will experience feelings of shame and self-blame. But when these feelings become chronic, they can interfere with our clients lives. So, how can we help clients overcome shame?

Imagine, for a moment, that a young child is reaching out to touch the stove.

Their parent comes running in, yelling, “No! No, don’t touch that!”

Often, in this situation, the child will start crying. They may run away and hide, if they can, or freeze where they are.

That is because this child is experiencing shame.

What is Shame?

Shame is a powerful emotion caused by a sense of embarrassment about the self. People who experience shame may feel humiliated, worthless, or afraid that someone will find out how inherently bad they are.

According to Richard Schwartz, PhD, shame is a two-part phenomenon: first, there is an inner critic that says, “You are bad.” Second, there is a younger part that believes it.

Left untreated, this can become a toxic cycle of depression and anxiety. . .

. . . but not all shame is toxic.

Think back to the child reaching for the stove. According to Janina Fisher, PhD, shame come online at the age when children begin to walk because, “as soon as they have that ability to explore, they have that ability to endanger themselves.” In this case, shame is adaptive. The feelings of embarrassment and fear stopped the child from engaging in the dangerous activity – touching the stove – and the memory of that shame will remind them not to put themselves in danger in the future.

Guilt vs Shame

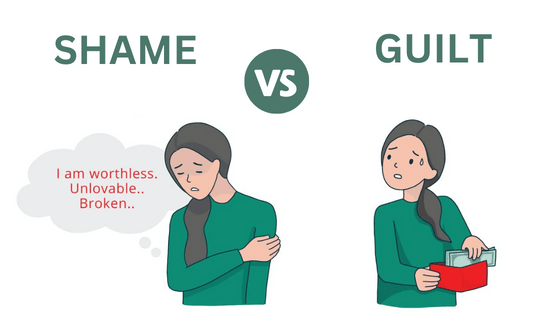

What is the difference between guilt and shame? Guilt is a feeling that “I’ve done something bad” whereas shame is a feeling that “I am bad.” In other words, when someone experiences shame, they feel they are somehow fundamentally flawed.

What is the difference between guilt and shame? Guilt is a feeling that “I’ve done something bad” whereas shame is a feeling that “I am bad.” In other words, when someone experiences shame, they feel they are somehow fundamentally flawed.

Some experts, like Brené Brown, PhD,[1] refer only to toxic shame as “shame” whereas the adaptive and protective forms may be considered “guilt.”

The Neurobiology of Shame

What happens in the brain when someone experiences shame? Two key areas of the brain are activated by shame: the prefrontal cortex and the posterior insula.

The prefrontal cortex is the part of the brain associated with moral reasoning. This is where judgements about the self occur.

The posterior insula is the part of the brain that engages visceral sensations in the body. According to Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD, this is likely related to the “pit in your stomach” feeling many people associate with shame.

Feelings of shame can also cause the brain to react as though it were in physical danger. This may activate the sympathetic nervous system and trigger defense responses like fight, flight, or freeze.[2]

Shame is often associated with the desire to become invisible or disappear. As Bessel van der Kolk, MD, describes, “People who feel this quality of shame go through the world hiding.” This is a manifestation of the flight response.

Where is Shame Held in the Body?

While many people have a physical response to shame, different people hold shame in different parts of their body. Clients commonly report feeling a pit in their stomach, tension in their shoulders, or discomfort on their skin.

There are also three common physical cues that can help therapists detect the presence of shame:

There are also three common physical cues that can help therapists detect the presence of shame:

- Downward Gaze

- Difficulty Making Eye-Contact

- Slumped Posture

These cues are important because it can be difficult for clients to talk about shame. After all, the nature of shame is to hide the undesirable parts of oneself. That’s why Ruth Lanius suggests asking about these symptoms in order to help clients talk about their shame. Questions like, “What is it like for you to look someone in the eye?” or “How would it be different to sit up straight?” allow clients to associate the physical symptoms with their internal emotions – and ultimately, better process the experience of shame.

It may be helpful to work with shame in the body in other ways, as well. For example, posture.

According to Peter Levine, PhD, “When a person is in a posture of shame, the shame aspect will continue until you’ve changed the posture.”

So, what is the opposite of shame? Someone who feels confident in themselves often feels pride. While a shame posture tends to be slumped over, pride often leads the chest to open and the spine to straighten.

Of course, helping clients shift into a more prideful posture may not bring them to actually feel pride; however, it can disrupt the overwhelming sense of shame enough to help clients find perspective and begin to build self-compassion.

The Relationship Between Shame and Trauma

Shame arises as a survival response. Think back to the example of the child reaching for a hot stove – that shame will keep them from similar harm in the future. Similarly, if a patient believes their trauma was their fault, there is a possibility that they can prevent a similar threat in the future.

Many clients hold tightly to shame out of fear of being retraumatized – even when it wasn’t their fault.

Many clients hold tightly to shame out of fear of being retraumatized – even when it wasn’t their fault.

But this shame can also leave clients with a fear of being fully seen by others. This can damage relationships and unravel a client’s support system, limiting their ability to heal.

So how can we help trauma survivors overcome these feelings of shame?

According to a study by Kerstin Jung, PhD, and Regina Steil, PsyD, Cognitive Restructuring and Imagery Modification (CRIM) may be an effective strategy for overcoming trauma-induced shame.

The first step, cognitive restructuring, involves discussing the shame. What is the traumatic root of this shame? Where in the body is it felt?

Then, provide some psychoeducation around the root of the shame. This will vary from client to client; however, it may be helpful to have clients conduct their own research.

The next step, imagery modification, begins with guiding clients through a visualization of healing or renewal related to the trauma.

Finally, have clients call to mind the feelings of shame and any associated imagery. Slowly replace the negative imagery with the visualization of healing.

In this way, CRIM can both help clients change the way they see themselves and change the imagery they associate with their trauma.

How Compassion Can Help Clients Overcome Shame

Compassion can be another key factor in helping clients break free of a painful cycle of shame and self-blame.

That’s because, according to Paul Gilbert, PhD, shame is often the result of our three emotional regulation systems becoming imbalanced.

Many people spend the majority of their time in their drive system, which focuses on achieving goals and accomplishing tasks, and their threat system, which focuses on protection, safety, and survival. But the third system of emotional regulation, the soothing system, becomes underdeveloped. Self-compassion can build that soothing system, allowing clients to slow down, soothe, experience kindness, and reduce shame.

So how can we help clients practice self-compassion?

According to Paul Gilbert, it may be helpful to start self-compassion practices with a three-step reality check:

- We don’t choose how our brains think

- We don’t choose how and in what context we’re born and grow up

- We don’t design what’s happening at the present moment, so many things are out of our control

Understanding these three concepts can help clients release the shame they feel about situations that aren’t their fault. Then, it may be helpful to move into a more targeted compassion-based exercise, such as:

- “Compassionate Other” Imagery

- Compassion-Enhanced Exposure Therapy

- Psychoeducation and Metaphors

- Mindfulness Meditation

As Laura Silberstein-Tirch, PsyD[3] says, “Compassion-focused therapy teaches clients to use compassionate self-correction, rather than shame-based self-attack.” By resourcing clients with the compassionate alternative, they can begin to release the shame and self-blame in a safe way.

Moving Forward with Shame in Therapy

Shame is one of the most common – and one of the most difficult – emotions to work with in therapy. That’s why it’s so important to have a full toolkit for helping clients overcome shame and self-blame.

When you help someone heal from shame, you change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References