How Trauma Affects Relationships

Among the many impacts of trauma is the damage it can cause to a client’s relationships. So how can we help clients foster stronger relationships that can be key to their healing?

All trauma is relational.

On the surface, that statement may sound counter-intuitive or overgeneralized. After all, you can probably think of traumatic experiences that don’t appear to be relational.

What if someone gets lost in the woods and is mauled by a bear? What if someone had to survive alone in the middle of the desert? How do these traumas effect relationships?

Well, according to Kelly Wilson, PhD, the nature of the event itself is only part of the lingering impact of trauma.

What’s more important is the meaning that the client derived from the event. Because it’s that meaning that can influence how clients see themselves among their peers.

Why All Trauma is Relational

To better understand why all trauma is relational, we must first make two key distinctions between specific types of trauma:

1. Shock vs Strain Trauma

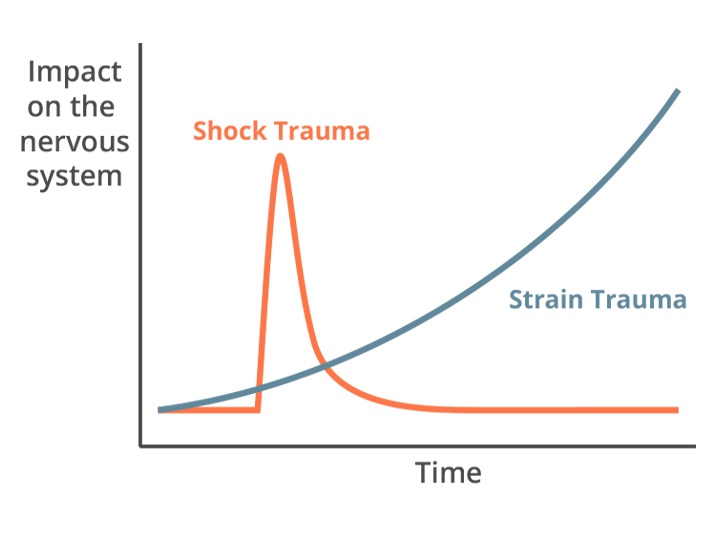

There are certain types of events people commonly recognize as traumatic – violence, major injury, sexual assault, or even a car accident. With shock trauma, events like these can have a profound impact on the nervous system in a very short time.

There are certain types of events people commonly recognize as traumatic – violence, major injury, sexual assault, or even a car accident. With shock trauma, events like these can have a profound impact on the nervous system in a very short time.

Strain trauma, on the other hand, is an accretion of events, often at a cultural level, which gradually become internalized. One all-too-common example is the trauma of racism. And what’s harder, as Thema Bryant-Davis, PhD describes, is the impact of strain trauma is often actively denied by others, adding another layer of relational strain.

Of course, sometimes trauma can both shock and strain the nervous system.

Take our earlier example of being mauled by a bear. The experience itself is a shock trauma; however, when it comes to going back into society, there won’t be many other people who can relate to surviving a bear attack. As such, pervasive feelings of loneliness, isolation, and not belonging can strain the nervous system further.

2. Intrusive vs Negligent Trauma

Like shock trauma, intrusive trauma is often more easily recognizable because it is experienced as a violation. Of course, a violation can be physical, sexual, verbal, or even emotional.

With intrusive trauma like microaggressions, there is distinct overlap with strain trauma, whereas a singular instance of physical assault may overlap more with shock trauma.

Negligent trauma, on the other hand, more often overlaps with strain trauma. You see, when someone has been abandoned or otherwise neglected, this creates a lack of human connection – and possibly other basic human needs – which becomes more intense the longer it is experienced.

So, while trauma is often caused within a human relationship – be it a primary caregiver, romantic partner, or violent stranger – the relational aspects of trauma also come into play in the aftermath. . .

. . . and it can impact every future interaction.

How Polyvagal Theory Explains Trauma and Relationships

According to polyvagal theory, the nervous system will first try to regulate a potentially traumatic situation using relational cues: facial expressions, vocalizations, and language.

This is called the activation of the social engagement system.

Unfortunately, the social engagement system can only come online while someone is within their window of tolerance, meaning they have to view the threat as manageable given their current skills and resources.

When a client leaves their window of tolerance, the nervous system moves into a state of defense. As Stephen Porges, PhD, explains, “The first primary defense we use is our physical strength. We fight or flee, and that makes us combative. It doesn’t make us lovers.”

Now, after trauma, clients are often living in a constant state of threat . This can make it difficult to maintain healthy relationships, meaning the therapeutic relationship may be one of the strongest interpersonal connections a client has.

How to Build a Strong Therapeutic Relationship

As therapists, our role is to witness the client’s experience, be present in the session, and build a relationship that can help reengage the social engagement system.

But Kelly Wilson, PhD, suggests that the conversation in therapy can become a bit of a tennis match – moving back and forth between question and answer reflexively rather than taking the time to actually process the conversation.

That’s why he uses a technique he calls, “Inhabiting Questions.”

So, after asking a question, he recommends the client actually hold off on answering for a given period of time. By allowing the client enough time to actually hear the words and to process their response before sharing it, we can communicate a dedicated, compassionate presence.

So, after asking a question, he recommends the client actually hold off on answering for a given period of time. By allowing the client enough time to actually hear the words and to process their response before sharing it, we can communicate a dedicated, compassionate presence.

Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD, also suggests that because intrusive trauma often comes from positions of power, it may be important to balance the power dynamic between therapist and client.

Of course, this dynamic is established from the very first interaction. That’s why Ruth suggests, if you’re comfortable, introducing yourself by your first name like you would with a peer. But you can manage the dynamic at any time by giving a client a little more control during a session.

Simple questions such as, “Where would you like to sit?” can go a long way in helping clients build a sense of agency in the therapy office. Ending with questions such as, “What do you need to feel safe and grounded before you leave?” can also help to build trust with clients, and allow them leave feeling empowered rather than dependent.

Working with Defense Responses in Relationships

When someone is triggered, especially if they have a history of trauma, they will move into a state of defense. As Janina Fisher, PhD, points out, “Even the healthiest of us have hurt places that are going to get triggered by our significant others.”

Now, this is commonly the fight-or-flight response, but there are many other threat responses they might fall into instead, including:

In couples therapy, it may be helpful to ask the partner how they interpret the response. For example, if someone begins to freeze during an argument, the partner may come to the conclusion that, “They’re ignoring me.” Or if after a rough day at work, someone goes straight to bed, the partner may believe, “They’re pushing me away.” This may also help to uncover some resentment between the partners.

In couples therapy, it may be helpful to ask the partner how they interpret the response. For example, if someone begins to freeze during an argument, the partner may come to the conclusion that, “They’re ignoring me.” Or if after a rough day at work, someone goes straight to bed, the partner may believe, “They’re pushing me away.” This may also help to uncover some resentment between the partners.

Now, these defense responses can be a prime source of shame for the person experiencing them as well – especially when clients can’t pinpoint why they would have such a reaction.

That’s why, for both partners in the relationship, Ron Siegel, PsyD, suggests starting by explaining why it might have been helpful to develop this response, why it made sense given the circumstances, and acknowledging its role in past survival.

According to both Janina Fisher, PhD, and Terry Real, MSW, LICSW, it may also be helpful to take an Internal Family Systems approach.

You see, when a couple gets together, it’s often because their wise, adult minds recognize that this is someone who they could build a good life with. But what neither of them realize is, every wise adult has their child selves inside them. . .

. . . and they might not be as compatible.

Especially when someone has experienced trauma, there is an exiled part, often called a “wounded child” where the pain and the hurt lives. But because that child part is so hurt and overwhelmed, another part, a protector, is necessary. This protector is often called the “adaptive child,” and it is this part which tends to surface in arguments and cause problems in relationships.

In order to heal these parts and engage the wise, functional adult in the relationship, we have to first address the protector part, and get permission to work with the wounded child.

Attachment Trauma and Intimate Relationships

Bessel van der Kolk, MD, suggests that attachment trauma can be a form of procedural learning. That’s because as humans, we spend the first few years of our lives entirely dependent upon a caregiver.

You see, we’re all biologically wired to seek attachment figures[1] at a time of stress. So, when a primary caregiver was abusive, a client is more likely to choose a similarly toxic romantic partner.

Furthermore, in cases of inconsistency from a caregiver, where cues of safety were later undermined by threat, the association can trigger threat systems when presented with legitimately good and caring romantic partners.[2]

Breaking the Cycle of Toxic Relationships

So how can we help clients break free from a vicious cycle of unsatisfying and potentially damaging relationships?

-

Address Underlying Shame

-

Process Underlying Trauma

-

Practice Self-Compassion

-

Expand the Window of Tolerance

-

Try Behavioral Experiments

Psychoeducation can be helpful in this process to explain that it is the body and the nervous system, not conscious judgement, that keeps choosing bad partners.

EMDR, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, and many other evidence-based trauma therapies can be helpful in working with a client’s attachment ruptures.

By resourcing clients with techniques like compassionate-self or compassionate-other imagery, we can help clients avoid falling back into a shame spiral.

Roleplaying self-advocacy, such as setting boundaries, and modeling safety in the therapeutic relationship can help increase a client’s ability to tolerate compassion from others.

By organizing a series of low-commitment interactions with others, clients can continue to widen the window of tolerance and build confidence for future relationships.

These are just a few ways to begin helping clients build stronger, more fulfilling relationships.

Of course, the consequence of doing any therapeutic work with couples is that, in some way, relationships will change. Clients have to be aware of and okay with that for there to be any sort of lasting results.

And remember. . .

. . . when you help someone heal from trauma, you can change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References

Want more ideas and strategies you can use with your clients today?

To learn more about the impact of trauma, and key strategies for moving forward in relationships, check out one of our courses:

The Advanced Master Program on the Treatment of Trauma

12 CE/CME Credits Available

Working with the Pain of Abandonment

4.25 CE/CME Credits Available

Working With Core Beliefs of “Working with the Fear of Rejection”

3 CE/CME Credits Available

How to Work with a Client’s Emotional Triggers

4 CE/CME Credits Available