Trauma-Informed Care

Trauma can have far-reaching impacts that are often difficult to detect. But with a trauma-informed approach, we can better understand how trauma has shaped a client’s life, determine the best path for healing, and avoid potentially retraumatizing.

How can we recognize trauma that doesn’t look like trauma?

Consider this . . .

A young boy is struggling to pay attention in his second-grade class. He makes careless mistakes on his schoolwork, is constantly fidgeting, and often speaks out of turn. As a result, the teacher identifies this child as “misbehaved,” and decides to call his parents. What that teacher doesn’t know is this boy’s parents have been fighting at home. Perhaps his mother is often drunk, or his father is violent, and by calling them, the boy’s home experience will only worsen.

Take another example . . .

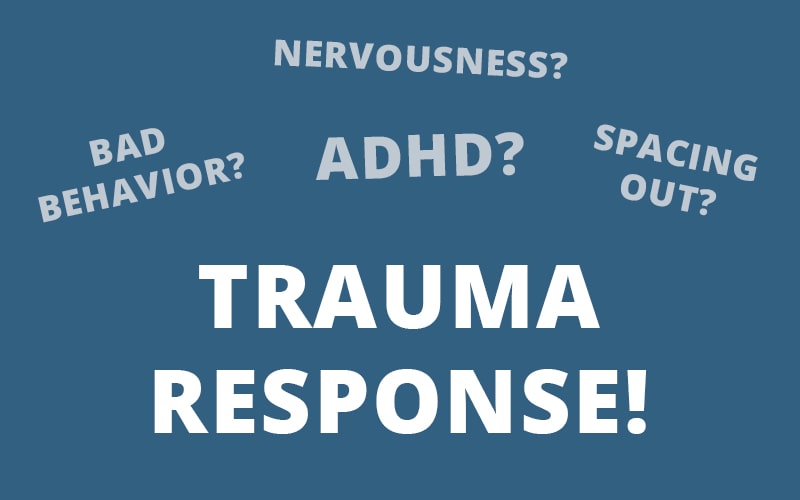

A woman goes to the gynecologist for a routine visit. As the doctor is beginning the examination, this woman’s voice shifts, sounding like a little girl — or maybe, she stops responding to the questions altogether. Some doctors may dismiss this behavior as “spacing out” or standard nervousness, but often, this is a key indicator of dissociation.

The Importance of Trauma-Informed Care

Because of the prevalence of trauma – and the different impacts it can have on each client – providing trauma-informed care is especially important.

Our examples from before are just two ways trauma can impact different parts of a client’s life. But when someone has been traumatized, they don’t get to pick and choose where they bring it or what triggers them. That’s why recognizing the prevalence of trauma has to be one of the first steps to adopting a trauma-informed approach to care.

According to the National Center for PTSD[1], about 60% percent of men and 50% percent of women experience at least one trauma in their lifetime. It is also estimated that 7-8% of the United States population will have PTSD at some point in their lives.

And for many clients, their traumatic experiences occur in childhood. A study led by Victor Carrión, MD[2], found that 67% of children have experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) — and their trauma responses are often misdiagnosed as ADHD or even simply “bad behavior.”

It was trauma expert Resmaa Menakem, MSW, LICSW, SEP who said that “Trauma decontextualized in a person will look like personality.”

So to truly understand how trauma is impacting a client, we need a shift in focus from “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?”

6 Principles of Trauma-Informed Care

There are six principles of trauma-informed care[3] that allow clinicians to effectively recognize and respond to the signs and symptoms of trauma.

This may be something you’ve already seen, but just as a refresher. . .

The guiding principles of trauma-informed care include:

- Safety – This is perhaps the most predominant principle of trauma-informed care, as a lack of safety could result in retraumatization. The physical setting, along with the interactions between client and clinician, must feel physically and psychologically safe . Every client comes with their own unique triggers and responses to trauma, so it’s up to the therapist to establish safety and continually monitor that the client feels secure in session.

- Trust and Transparency – Many people who have experienced trauma live in a constant state of uncertainty or mistrust , so it’s critical to build and maintain a trusting relationship with clients. Part of this includes being honest and transparent about the goals of treatment. Explaining to clients the type of care you will be providing can go a long way toward earning their trust.

- Peer Support – For clients who have experienced trauma, interactions with other trauma survivors can often foster hope and promote healing through a sense of common humanity. Sharing their stories can help to establish safety, build trust, and enhance collaboration.

- Collaboration – In addition to letting clients know about types of treatment and outcomes, therapists should let clients play an active role in decisions regarding their own treatment. This collaboration between client and clinician allows the client to take responsibility for their care and needs while working with the clinician to determine the best treatment plan. This process also helps to balance the level of power between clinicians and clients.

- Empowerment & Choice – Clients should be encouraged to share their stories while being listened to and acknowledged. While recognizing that their voice may have been diminished or silenced in the past, it’s important to allow them to speak their truth and give them control over their own story.

- Cultural, Historical, and Gender Awareness – Being aware and respectful of the differences that exist between yourself and your clients is important to ensuring their comfort and safety during treatment. The cultural needs or requests of each client should be accommodated, and therapists should avoid making assumptions about a client’s cultural or gender identity.

How to Apply Trauma-Informed Care Principles in Treatment

So now that we’ve seen the core principles of a trauma-informed approach, here a few ways those principles can be incorporated into clinical treatment:

Screening

An initial screening can inform the remainder of a client’s therapy. A trauma-informed therapist understands the prevalence and widespread impacts of trauma and will take a comprehensive developmental history in early sessions. This can help identify which approaches may be necessary for a specific client.

But it’s important to remember that not every client who is suffering from trauma knows that trauma is part of the problem. For example, many clients don’t think of themselves as having suffered abuse or neglect.

So instead of asking about abuse or neglect in general terms, it can be helpful to ask clients more specific questions like, “Was there ever a time when someone made you feel worthless?” or, “Was there ever an experience that left you deeply upset or troubled?” or even, “Was there a time when you needed someone, and they weren’t there for you?”

Based on the client’s answer, you can then explore those events to the extent that the client is comfortable doing so.

If the client responds with a “no” to your questions, it’s important to remain open to the possibility that trauma may exist, but the client either isn’t aware or isn’t yet ready to disclose. It would then be appropriate to rescreen the client as therapy continues and the relationship continues to grow.

In either case, the key is to let clients decide what, how much, and when they are going to share. Pushing too hard for information can negate feelings of safety – and potentially retraumatize.

Safety

When someone has experienced trauma, their sense of safety can become skewed.

So, let’s say a client does share a traumatic experience. Should we immediately begin to investigate?

Diving into a traumatic memory too soon, without first creating a sense of safety or resourcing clients, could damage the therapeutic relationship or worse – cause harm. So before we can help clients process traumatic memories, creating a sense of safety is key.

Here are a few things to be mindful of when considering safety from a trauma-informed perspective:

- Eye contact – As humans, we tend to engage in eye contact instinctually. Between an infant and a caregiver, it can be a major part of developing attachment and bonding. Later in life, it makes a conversation more persuasive and memorable. Therapists often intuitively utilize eye contact to activate the social engagement system and help clients feel validated. But for a client with a history of trauma, direct eye contact may appear threatening, perhaps even triggering fight, flight, freeze, or any other defensive response. One way to work around this, according to Peter Levine, PhD, is by placing two chairs at a 45-degree angle, rather than directly facing each other. That gives the client the option to look at the therapist or face straight ahead and avoid direct eye contact.

- Prosody – In addition to eye contact, prosody can be a critical factor when working with clients who have experienced trauma. An effective use of pacing, rhythm, intonation, volume, and tone of voice can be key for conveying empathy, building trust, and establishing safety. According to Stephen Porges, PhD, clients who have experienced trauma often interpret loud, low-frequency sounds as threats. So to reduce the chances of triggering a client’s trauma response, it is recommended to avoid using a loud voice or fast, short, and choppy sentences.

- Facial Expressions – Like eye contact and prosody, facial expressions are another microbehavior that can inspire feelings of safety or evoke feelings of danger. According to the Polyvagal Theory, our facial muscles are linked to the vagus nerve and are part of the social engagement system. So the expressions we have on our faces as therapists are communicating directly to clients and influencing their levels of safety and trust. Likewise, therapists can learn a lot from clients by continually monitoring their facial expressions. A common example would be flat affect, which signals a lack of engagement and is a clear indicator that something is wrong.

- Proximity – For some clients, proximity or closeness may have preceded their traumatic event and can be especially triggering, so it’s critical to understand where and how they will feel comfortable and safe in your office. That may include repositioning yourself or even rearranging the furniture in your office to accommodate their needs. At the beginning of each session, you could ask, “Where would you like to sit today?” That simple question can be empowering and promote a sense of agency.

Treatment Plan

After establishing a sense of safety in the therapeutic relationship, you can then move forward with a trauma-informed treatment plan.

Let’s revisit the change in focus that we mentioned earlier, shifting from “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?”

That simple shift in mindset can have a profound impact on the collaborative treatment plan that you design with your client.

Let’s say, for example, that a client comes to therapy because of issues they are having in their relationship. After exploring some instances where these issues arose, a pattern started to appear where a few certain behaviors seemed to be the cause of these issues.

Now, it could be relatively easy to focus on changing those few behaviors that are causing problems in their relationship.

But as a trauma-informed therapist, the focus would instead be on what happened that’s driving the behaviors in the first place.

Perhaps the client is reenacting a pattern of behavior that they witnessed from their parents when they were a child. Maybe these same behaviors are also causing problems in the client’s work life, but the client sees that as an entirely separate issue that they didn’t feel the need to disclose.

So if we focused solely on the behaviors that were damaging the relationship, but didn’t uncover the underlying reasons for the behaviors, we would not only miss a critical aspect of the client’s past – we would miss how that is impacting other areas of their life.

By adopting a trauma-informed approach, we’re not only seeking out how clients have adapted and reacted to their traumatic experiences, but we’re also focusing on the widespread impact of those adaptations and reactions so that we can offer treatment that encompasses all aspects of the lives.

A Trauma-Informed Approach to Working with Racial Stress

Racial stress is an all-too-common source of trauma for clients – and must therefore be at the forefront of our approach to working with trauma.[4]

As you know, trauma can either be one deeply impactful event, or a repetitive stress. But for some clients, especially those of color, the repetitive stress they face is systemic.

One example we often hear about is microaggressions. But from a trauma-informed perspective, a better term might be “racial trauma encounters.” And sometimes, these encounters even occur in our office.

The majority of therapists’ training – especially in the United States – is based in a white, Eurocentric approach. So sometimes, the therapeutic approaches we believe would be most helpful for a client actually de-validate their cultural experiences.

Consider a client who has trouble asserting their needs in relationships. This might be an adult client who serves as a caregiver to their elderly parents, and they often sacrifice their own social life or career aspirations in order to continue personally handling that care. We are often quick to fit certain labels, like codependency, to that client’s experience. From an individualist standpoint, the solution may be working with that client to establish more concrete boundaries, perhaps even hiring a different caregiver for the parents.

But, say the client is from a collectivist culture with heavy values on familial relationships. Such suggestions may undermine the client’s personal values, disrupting the solid foundation on which they can build decisions in times of uncertainty. So, without understanding the cultural nuances, we might unintentionally cause the client more harm.

But, say the client is from a collectivist culture with heavy values on familial relationships. Such suggestions may undermine the client’s personal values, disrupting the solid foundation on which they can build decisions in times of uncertainty. So, without understanding the cultural nuances, we might unintentionally cause the client more harm.

Here’s another way to think about it, further expanding upon the shift in focus that was raised earlier . . .

According to Thema Bryant-Davis, PhD, society would look at a person’s problems and ask, “What’s wrong with you?” A trauma-informed therapist would ask, “What happened to you?” A multicultural trauma-informed therapist would ask, “What happened to you in your community?”

This is how we can build trust with clients and get to the root of their trauma history.

We cannot claim to provide trauma-informed care unless that work is inclusive of all types of trauma our clients may face. And while we can’t overturn the systemic barriers to care overnight, taking the time to continuously re-evaluate our practices and foster our own cultural humility can make a major difference in our clients’ experiences.

Moving Forward with a Trauma-Informed Approach

Trauma-informed care cannot be achieved through a singular training or filling out a checklist. It requires constant attention and re-evaluation. But there are four key assumptions you can adopt moving forward:

- Realize how widespread and powerful the impact of trauma is.

- Recognize the signs of trauma.

- Respond by fully integrating trauma-informed strategies into personal and organizational work

- Resist Re-traumatization by avoiding creating an unnecessarily stressful or triggering environment

With the right care and support, trauma doesn’t have to be a life-sentence for our clients.

And remember. . .

. . . when you help someone heal from trauma, you can change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References

Want more ideas and strategies you can use with your clients today?

To learn more about the latest strategies for trauma treatment, check out one of our courses:

The Advanced Master Program on the Treatment of Trauma

12 CE/CME Credits Available

The Treating Trauma Master Series

10 CE/CME Credits Available

Integrating Compassion-Based Approaches into Trauma Treatment

3.25 CE/CME Credits Available

Why the Vagal System Holds the Key to the Treatment of Trauma

2 CE/CME Credits Available