How the Nervous System Responds to Trauma

The nervous system’s defense responses can be critical for surviving trauma – but once the threat is gone, they can quickly become maladaptive. So, how can we work with these defenses to help clients heal from trauma?

Consider this short example. . .

A young girl lives with her parents. Her mother is a workaholic and is rarely at home, so her father stays home to take care of her. But the father is resentful, both of his wife and this young girl, for getting in the way of his ambitions. Sometimes his anger turns violent – especially when he’s been drinking.

Since she is often home with her father, this girl is usually the recipient of this anger. Even so, she relies on her parents for her basic needs, putting her in a position of chronic distress.

So how can this young girl survive in this unstable and threatening environment?

How Polyvagal Theory Explains Threat Responses

When working with clients’ threat responses, it can often be useful to view them through the lens of polyvagal theory.

You see, for us to even exist right now, our ancestors had to succeed in their struggle for survival – and luckily for us, they passed on some of their tricks.

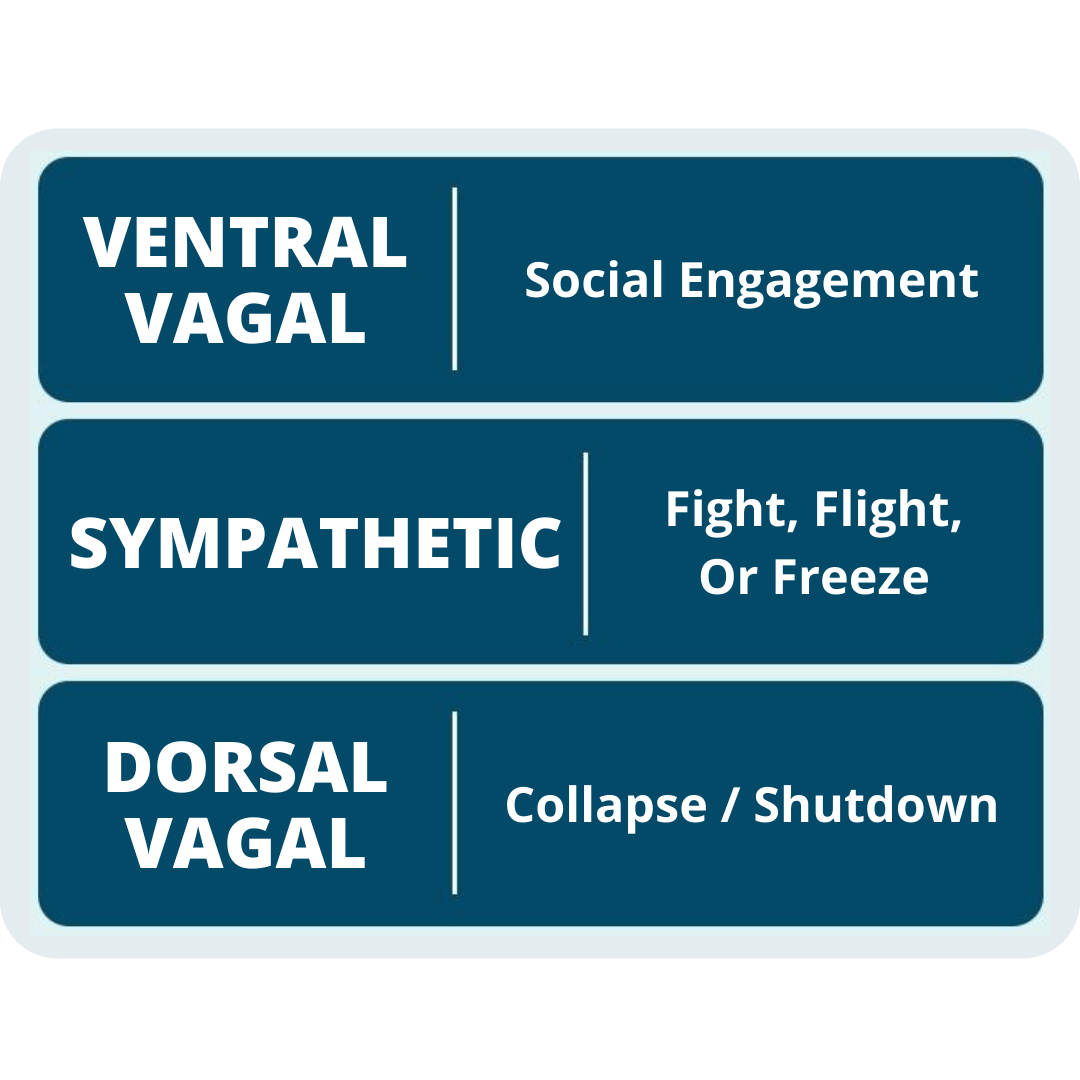

According to Stephen Porges, PhD, the nervous systems of mammals have developed three autonomic nervous system responses to threat: social engagement, sympathetic mobilization, and parasympathetic immobilization.

Each of these nervous system responses was acquired at a different point in our evolutionary history, and they can all be effective for mitigating threats or helping us survive certain traumatic experiences.

But once the nervous system discovers that a particular response works, neurological connections are strengthened, and the response is more likely to be repeated.

Not only that, but when a client experiences trauma, their nervous system becomes primed to detect threats – making it all the more likely that their defense response will be activated.

Tara Brach, PhD, once said, “All creatures are in a day-to-day struggle with the sense of, ‘I need to survive.’”

But for clients who experience trauma, like the girl from our example above, the intensity of that struggle to survive is increased exponentially.

When the Social Engagement System Responds to Trauma

Humans currently rely, first and foremost, on the social engagement system for survival.

Humans currently rely, first and foremost, on the social engagement system for survival.

This method of using the face, voice, and language to mitigate a threat is one of the newest additions to our defense toolbox, and it is unique to mammals.

Of course, like many mammals, humans are social creatures. That’s why, as Bessel van der Kolk, MD, says, “The more scared we are, the more we have a need for companionship.” But we don’t all go about it in the same way.

You see, experts have identified at least three distinct ways we attempt to use threat mobilization as a coregulatory activity:

-

Attach/Cry for Help

From the time we are born, we have the ability to cry.

It’s one of the earliest adaptive responses we have. In fact, babies’ cries are so effective in getting support from adults that other creatures, such as cats, have learned to mimic them.

But as adults, the inclination to cry for someone to help us doesn’t go away.

Of course, the attach/cry-for-help response isn’t the same as what we do when we’re upset after a long day at work, asking for a hug or a shoulder to cry on. Like an infant’s cry, it’s much more visceral. As Pat Ogden, PhD, puts it, attach/cry carries this sense that, “I’m not going to survive unless you take care of me.”

Let’s think back to our earlier example of the young girl. There is certainly a life-or-death quality to her predicament: she needs her father to provide her basic needs, but there is simultaneously the threat of abuse.

In this case, that girl may begin to cling to her mother, constantly calling her at work, or perhaps she would display her desperation to a trusted teacher.

For some clients, the person they can attach and cry to may even be a therapist.

So how can we work with clients who have a tendency towards the attach/cry-for-help response?

According to Janina Fisher, PhD, the key may lie in what she refers to as “right-brain communication.”

Now, right-brain communication is about going beyond words alone to better communicate with a patient. It involves non-verbal cues such as facial expression, eye contact, and tone of voice to express presence and understanding on a more somatic and emotional level.

Once that connection between nervous systems has been established, it will be easier for a therapist to hold boundaries without seeming confrontational.

It may seem counterintuitive, but despite any instincts we may have to be there for these clients, we can’t be accessible 24/7. And even if we could, we would only inhibit their ability to learn how to be there for themselves.

There are, however, many ways we can resource these clients with strategies to become more self-reliant. For example, Christine Padesky, PhD suggests a strengths-based approach. By helping clients find where they’re already succeeding in life, even somewhere small, and building a model of how to apply that to life’s bigger challenges, we can help foster lasting resilience.

-

Please and Appease

Sometimes called the “fawn” response,[1] the idea of please and appease is that by “getting on the good side” of the source of the threat, the danger will lessen. This may involve simply maintaining enough vigilance to not activate the perpetrator’s nervous system, or engaging in strategies to actively calm the nervous system.

Please and appease is particularly effective in situations of repetitive abuse or other recurring trauma.

Take our example of the young girl and her father.

If she comes home with a failed test he needs to sign, this will likely trigger his anger and resentment. But when she’s obedient, or perhaps even goes out of her way to make him look good in front of his friends, he will be less likely to take out his frustrations on her. So, she attempts to please and appease him at all times.

Of course, as Thema Bryant-Davis, PhD, points out, a please and appease response can add an extra level of complexity to our work as therapists.

You see, clients can’t usually leave their patterns of pleasing and appeasing at the door. So, in the therapeutic relationship, they may feel a need to be a good client. And this is a slippery slope because good clients make us feel like good therapists.

But when the therapeutic progress comes from a state of defense, there hasn’t really been progress.

So how can we help clients who please and appease?

- Ask Questions. “Is that what you would think if you were on your own?”

- Give Permission. “Your range of emotion does not end where others can tolerate it.”

- Practice Compassion. “No human being is worth more than another, including you.”

- Challenge Other-Based Esteem. “You have worth, even when no one says you do.”

- Roleplay Relational Empowerment. “I appreciate your input and why you think that. I saw it a different way.”

-

Tend and Befriend

According to Janina Fisher, PhD,[2] the please and appease response is likely an adaptation of another defense: tend and befriend.

When it was first introduced, tend and befriend was described as a stress response for women. And while we now know and recognize that men and non-binary individuals can also experience the tend and befriend response, the way women are socialized in western culture makes them particularly susceptible to this response.

You see, women are often taught to exist in relation to others, and to regulate through social interactions. This often internalizes a sense that personal value and self-worth are based on what we contribute to society.

So, when faced with a stressful situation, some people are simply primed to think of the plight of others. As such, the sympathetic mobilization that would normally trigger fight or flight is channeled into compassion.

Of course, compassion is generally a good thing. We even have an internal rewards system which is activated when we have helped others, naturally reinforcing compassionate practices so we will repeat them.

But when compassion for others interferes with the ability to care for oneself, this response can actually create more stress and trauma long-term.

So how can we help clients who overly tend and befriend?

Metaphors can be useful in helping a client gain perspective. For example, if you’ve ever been on an airplane, you’ve probably heard the flight attendant talk about what to do if the cabin loses pressure: “Oxygen masks will descend from the compartment above you. Please be sure to secure your own mask before assisting those around you.”

The idea is, if you don’t have enough oxygen yourself, you won’t be able to effectively help others. The same applies in a stressful or traumatic situation.

When the Sympathetic Nervous System Responds to Trauma

Before the social engagement system developed, our ancestors relied on the sympathetic nervous system. When faced with a threat, it would release hormones such as adrenaline and epinephrine to help mobilize them against the threat in a number of possible ways.

Before the social engagement system developed, our ancestors relied on the sympathetic nervous system. When faced with a threat, it would release hormones such as adrenaline and epinephrine to help mobilize them against the threat in a number of possible ways.

And because not every threat can be tamed through interpersonal communication, the nervous system still reverts to this older set of strategies, depending on the threat it detects.

-

Freeze

You may have heard about freeze as an orienting response, or a state where, for a moment, the nervous system figures out where it is in relation to the threat.

While this sort of freeze certainly exists, we’ll be looking at something a bit different: a chronic freeze response. Also known as tonic immobility, this sort of freeze presents exactly as it sounds: a feeling of being frozen.

Of course, just because the body isn’t moving doesn’t mean it’s not activated. Freeze is still a state of hyperarousal. Heart rate and blood pressure have increased, the muscles are tense and full of energy, they just simply can’t release it.

And as Bessel van der Kolk, PhD, says, “You cannot do psychotherapy or psychoeducation when people are frozen, because when you’re frozen, nothing can come into your brain until the frozenness is stopped.”

So how can we help clients who are stuck in the freeze response to return to their window of tolerance?

According to Peter Levine, PhD, the key is to find a release for the stored energy.

Although, getting a frozen client moving isn’t the easiest endeavor. That’s why Stephen Porges, PhD, boiled it down to a two-step process:

- Remove cues of danger

- Sneak in cues of safety

But since a brain stuck in the freeze response can’t process the words we are saying, these processes need to communicate on the level of the nervous system.

For example, direct face-to-face eye contact may be perceived as intrusive, and therefore a cue of danger. So by looking down, to the side, or otherwise slightly averting our gaze, we can help clients recognize that we are not a threat.

Unfortunately, simply recognizing that the therapist isn’t the danger won’t automatically make the client feel safe enough to come out of freeze. That’s why Stephen recommends utilizing vocal prosody as well. The musical intonation of the voice is one of the few cues that can sneak through the body’s defenses.

In this way, we are re-engaging the social engagement system to override the freeze response.

-

Fight or Flight

When we think about responses to acute stress, fight or flight is often the first to come to mind.

You see, when we encounter a threat, the most adaptive response would be to not be there at all. So, if we can flee and avoid conflict altogether, there is no risk of trauma.

On the other hand, our nervous system understands that some threats are simply inescapable. So the same mobilization that would have been used to entirely avoid altercation is instead filtered into the fight response. While there is more risk of sustaining damage in a fight, there may still be the possibility of overpowering or weakening the threat to make escape possible.

But let’s think back to our example of the young girl. What would happen if she tried to flee?

As a child, she doesn’t have much in the way of money, and is too young to get a job, so she can’t provide for herself. Besides, if she tried, her parents might file a missing persons report and she’d be returned to them anyway.

And of course, her father is much bigger and stronger than she is, so attempting to fight him would simply cause more pain.

That’s why the nervous system has one final defense against trauma.

When the Parasympathetic Nervous System Responds to Trauma

Even before the sympathetic response developed, an early version of our vagus nerve controlled another response: parasympathetic immobilization.

Even before the sympathetic response developed, an early version of our vagus nerve controlled another response: parasympathetic immobilization.

When a threat is simply too fast, too strong, too cunning, or otherwise inescapable through a mobilization strategy, the nervous system still wants to protect us as much as possible.

-

Collapse Shutdown

Whether we call it collapse, shutdown, submit, or faint, this is the defense response of last resort.

You see, when it’s impossible to escape, fighting is futile, and the threat is just too imminent to otherwise mitigate, the body is still trying to find a way to survive the trauma with the least possible amount of damage.

According to Pat Ogden, PhD, this is a sort of death-feigning response in which the dorsal vagal system shuts everything down, from making muscles go limp to slowing breathing.

This may also involve another defense response, dissociation, allowing the client to be disconnected from the body that is experiencing the trauma. But as Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD, points out, “The dynorphins that help facilitate those out-of-body experiences are also associated with chronic feelings of depression.”

What’s more, if collapse becomes a client’s habitual response, it can actually leave them more susceptible to trauma. After all, as Deb Dana, LCSW, says, “If you are in that dulled, unaware state, you’re not taking in new cues of danger around you.”

So how can we help clients come out of this collapse/shutdown response?

- Working with the Body

By helping clients sit with an aligned spine and perform suppressed movements, like pushing away, we can physically counteract the collapse. We just have to be careful not to prime a client’s activation so much as to push them into another defense response. - Working with the Nervous System

By role-playing assertive defense strategies, we can help clients differentiate between the collapsed, dorsal vagal state, an over-energized sympathetic state, and the ventral vagal state from which they have the most power and control – also known as the window of tolerance.. - Working with the Mind

By helping clients reframe their perspective of the shutdown response to see it as adaptive, we can foster self-compassion and reduce the shame that keeps them in a cycle of learned helplessness.

- Working with the Body

Whether it be a childhood attachment rupture triggered in a romantic relationship or a natural disaster leaving an entire community struggling to care for one another, the trauma clients experience – and the responses that helped them survive it – can impact every interaction moving forward.

And remember. . .

. . . when you help someone heal from trauma, you can change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References

Want more ideas and strategies you can use with your clients today?

To learn more about how to work with trauma at the level of the nervous system, check out some of our courses:

Why the Vagal System Holds the Key to the Treatment of Trauma

2 CE/CME Credits Available

Advanced Master Program on the Treatment of Trauma

12 CE/CME Credits Available

How to Work with the Limbic System to Reverse the Physiological Imprint of Trauma

3.25 CE/CME Credits Available

The Neurobiology of Trauma

3 CE/CME Credits Available