Traumatic Memory

When someone has experienced trauma, it can impact every aspect of their life. So how can we help clients process their traumatic memories and begin to heal?

Imagine a war veteran has just returned home.

After a series of long deployments to the front lines of combat, they have not had the chance to fully process their trauma. Still, excited to be back with their family, they decide to go out for a large celebration.

But when the celebratory fireworks create sounds reminiscent of gunfire, this veteran is thrust back into the midst of war.

Suddenly, their only thought is, “How can I survive?”

Memory Systems in the Brain

At one time, this veteran’s experiences would have likely been called, “shell shock.” As you know, trauma wasn’t always well-understood.

But as researchers have learned more about post-traumatic stress, they have identified some key differences in the brain – and especially, in the brain’s memory systems – after trauma.

As Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD, has said, “Traumatic memory is not a memory that’s remembered, but a memory that’s relived. People will actually feel like the past is recurring. And this will happen at the level of mind, brain, and body.”

So, let’s step back to look at the formation of memory itself.

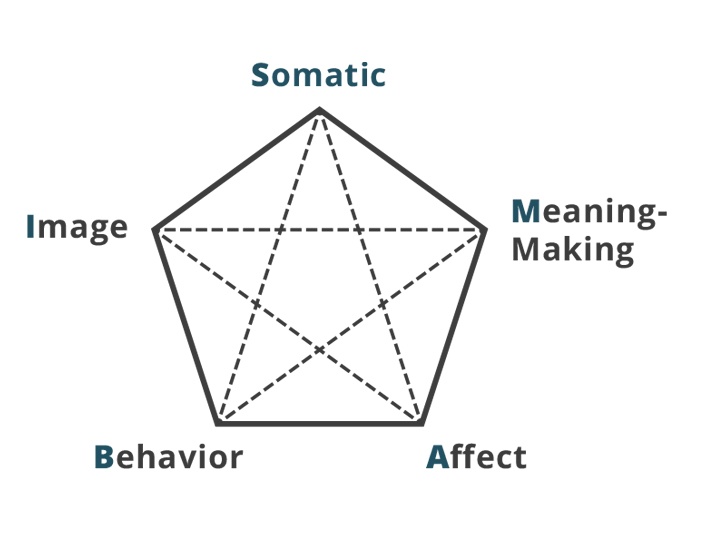

According to Peter Levine, PhD, there are 5 areas in which we typically gather, process, and store information. His acronym for this is SIBAM:

- Somatic –internal, bodily sensations.

- Images –sensations coming from outside the body, such as tastes, smells, touches, or sights.

- Behavior – voluntary gestures, facial expressions, postures, breathing, or other observable actions.

- Affect – primary emotions, such as anger, joy, sadness, and the contours, or more nuanced feelings, that guide us.

- Meaning-Making – cognitive thoughts and beliefs.

Hundreds of thousands of nerve fibers throughout the body collect all of this information and pass it along to the respective areas of the brain best optimized to process it.

Now, an ordinary memory system would let experiences pass through, integrating each new detail with the brain’s existing knowledge. In this way, the memory becomes consolidated within the context of the rest of the person’s experiences and beliefs about reality.

But as Bessel van der Kolk, MD, describes, “Trauma doesn’t fit in. Trauma lives on as an isolated piece of the past that keeps coming back.”

Think, for example, of our combat veteran.

During their deployment, they gathered all sorts of information – the somatic feelings of hunger, muscle soreness, and pain, the images of the enemy’s uniform and the smell of gunpowder.

But traumatic experiences like war are often too overwhelming to process the entire situation cohesively.

So in this veteran’s memory, the sound of a loud explosion may still be connected with the affects of fear or the somatic sensations associated with a threat response, like fight or flight. But these memories are isolated from the rest of reality – being home again with family, and the sensations that go along with that.

And when the sound triggered these intense responses, that lack of integration prevented the mind from being able to ground itself in the present.

How Trauma Impacts Four Types of Memory

Now, the different types of information we gather each go into forming different types of memory as well.

As you probably know, memories can be broadly divided into two categories: explicit and implicit.

Explicit Memory

Sometimes referred to as “declarative memory,” explicit memories are those which we can consciously recall.

- Semantic Memory includes general knowledge and facts.

- Episodic Memory includes autobiographical narratives of specific events or experiences.

But when trauma interferes, information (like words, images, and sounds) processed in different parts of the brain are prevented from combining into a cohesive semantic memory.

But trauma can shut down the episodic memory, isolating specific details or fragmenting the sequence of events. It may also make it more difficult to recognize which parts of a memory are self-relevant.

Implict Memory

On the other hand, implicit memories are those unconscious memories which live deep within the nervous system.

But after trauma, clients may get triggered and experience painful emotions all over again, often without context.

But a traumatic event may create new procedural memories, or change and override old ones, causing clients to tense up, change their posture, or experience sensations like pain or numbness.

When we’re looking at preverbal trauma, the effects are most often found in emotional or procedural memory. After all, implicit memories[1] can encode themselves even when someone isn’t old enough to cognitively process them.

Which means, clients may not even be aware that trauma is part of the problem.

Working with Flashbacks and Post-Traumatic Stress

The consolidation window, when fear memories are being established and strengthened in the brain, lasts approximately six hours after experiencing a traumatic event.

A study led by Victoria Pile, PhD, suggests that a strategy called “updating,” or providing guided, verbal context, can decrease the conditioned fear response associated with the development of PTSD.

Unfortunately, it’s rare that trauma therapy can be so prompt as to reach clients within six hours of an event. But while we may not always be able to prevent symptoms of PTSD, there has been some success with the “updating” technique in reducing symptoms of chronic PTSD as well.

But the memory itself isn’t the only thing that drives chronic PTSD.

Many clients also feel intense shame surrounding their symptoms, which may push them out of their window of tolerance and trigger a vicious cycle of flashbacks.

So how can we help clients escape the shame of post-traumatic stress?

Psychoeducation can be particularly useful in fostering self-compassion and reducing feelings of shame around traumatic memory.

For example, Bill O’Hanlon, MS, LMFT, often uses a simple metaphor to illustrate how trauma can alter a client’s sense of time, causing them to relive memories.

You see, in life, we each have a filing cabinet with three drawers.

The bottom drawer is the largest, and it holds the past. It’s stuffed full of every moment that has already happened, and all of the sensations and patterns to go with them. The next drawer is for the present. It only has one folder in it, the present moment, so it is a bit smaller. And the smallest yet, the top drawer, is for the future – although, it should be empty because the future hasn’t happened yet.

But trauma likes to mess with the filing system.

Suddenly, a bunch of the past folders are all stuffed into the present, and there may even be a few spilling out of the tiny future drawer.

Our role, as therapists, is to help clients refile these folders where they belong.

Not only does this metaphor help to reduce a client’s shame, but it provides a framework for visualizing a timeline.

In this way, we are reactivating the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the time-keeping part of the brain, so that clients can more easily identify a beginning, middle, and end of each event.

And knowing this is useful during flashbacks because, as Bessel van der Kolk, MD, says, “Anything is bearable as long as you know that it’s going to come to an end.”

Strategies for Processing Traumatic Memory

Bill O’Hanlon, MS, LMFT, has said, “The good news about brains is, they can change really quickly. The bad news is, they tend not to.”

But with the right tools, neuroplasticity can be the key to working with and reprocessing traumatic memory.

-

Brainspotting and Bilateral Stimulation:

-

Imagery:

-

Somatic Approaches:

EMDR, or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, has become rather popular for its efficacy in helping clients to process emotional distress.

EMDR, or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, has become rather popular for its efficacy in helping clients to process emotional distress.

Peter Levine, PhD,[2] criticizes typical EMDR trainings for being too activating due to the speed and proximity of the cues to the client’s face, limiting its benefits.

But with some modifications to the motions and speed, EMDR can shift from processing in a sympathetic state to a parasympathetic one. As David Grand, PhD, explains, “Because it is already such a powerful process, you don’t need clients to get any more activated than necessary.”

David also suggests that bilateral sound stimulation can be just as effective as EMDR while remaining in a parasympathetic state.

With most of these bilateral stimulation techniques, a traumatic memory is said to be sufficiently resolved when they reach a zero-activation level on the Subjective Unit of Disturbance Scale.

But according to David Grand, PhD, another technique can actually help process these memories on an even deeper level: brainspotting.

Rather than continuous eye movement, like in EMDR, brainspotting uses eye fixation. Basically, we stimulate movement until we find a place of activation – a brainspot – and then stay there.

The theory is that this bypasses the neocortex and drops down into the subcortical areas of the brain – the limbic system and the brainstem.

While brainspotting doesn’t inherently involve bilateral stimulation like EMDR would, David has found that combining brainspotting with bilateral sound cues can improve efficacy even further. By acting as a support to the window of tolerance, we can work with distressing memories at a much greater depth without triggering the client.

Recent research has shown self-compassion training to be one of the most effective ways to reduce both shame and PTSD symptoms.

As you know, guided imagery is a staple amongst compassion-oriented therapy techniques. During these meditations, we generally use a calm, prosodic voice to demonstrate cues of safety and keep the client regulated.

But for some clients, especially veterans suffering from PTSD, that tone is a little too far out of reach. In fact, as Belleruth Naparstek, LISCW, describes, sometimes it can even make clients feel angry or isolated and misunderstood.

That’s why it’s so important to adjust these practices in order to meet the client wherever they are.

Guided imagery doesn’t have to start soft and musical. One of the most effective introductions to a guided imagery tape is actually a recording of an army sergeant giving orders for a morning drill.

There are a couple different ways in which working with the body can influence memory.

For example, research led by Daniel Casasanto, PhD, and Katinka Dijkstra, PhD, suggests that spatial motor movements can shape the mind.

You’ve probably heard someone say that they’re “on top of the world,” or “down in the dumps.”

Humans tend to automatically associate upward with positivity and downward with negativity. And that association runs deep. You see, when clients did a simple action like rolling a marble in an upward motion, they found it much easier to recall positive memories. Similarly, rolling a marble downward primed clients to recall negative memories.

This “marble therapy” may be particularly useful in managing a client’s trauma narrative.

But as you know, not all memory is narrative. So how can we work with procedural memory rooted in trauma?

According to Pat Ogden, PhD, it begins with identifying patterns in the body.

She recommends encouraging the client stay with a pattern, perhaps even exaggerating it if they have a large enough window of tolerance, to discover what emotions or memories come up. Then, as we communicate with those hurt parts, we can simultaneously resource the body with guided breathing and posture exercises to shift it out of the pattern.

Moving Forward

These are just a few examples of how we can work with traumatic memory to help clients heal. As research continues, new strategies will emerge so we can better help clients.

And remember . . .

. . . when you help someone heal from trauma, you can change the course of civilization. That’s because it’s not just that person’s life that changes, but that healing can also have an impact on their spouse, their children, and their friends and colleagues. And that can ripple out to their community, to their state and then to their country, and eventually to the world. What you do is so important.

References

Want more ideas and strategies you can use with your clients today?

To learn more about the latest strategies for treating Traumatic Memory, check out one of our courses:

The Advanced Master Program on the Treatment of Trauma

12 CE/CME Credits Available

How to Break the Cycle of Traumatic Memory

2 CE/CME Credits Available

How to Work with Trauma That Can’t be Verbalized

2 CE/CME Credits Available

Treating Trauma Master Series

10 CE/CME Credits Available